Hong Ming

Many contemporary Chinese associate the ancient concept of loyalty with those

government officials that foolishly or without questioning followed their emperors’

orders, even when they knew that those orders compromised their emperors’

and their country’s interests.

Many modern day Chinese falsely associate the ancient Doctrine of the Mean advocated

by Confucius with those so-called wise people who know what’s best for

themselves, safeguarding their personal security and playing it safe in this

insecure world by staying neutral, particularly when facing two polar factions.

When thinking of women’s social status in ancient Chinese society, many

contemporary Chinese think of those powerless Chinese women in the patriarchic

Chinese society. They were denied the means and opportunities to earn their

own livings. They were taught by men to believe that when they became widowed,

they should stay widowed for the rest of their lives, guarding their chastity

out of the respect for their deceased husbands. Even if they were destitute,

they were expected to starve themselves to death, rather than marry another

man who would provide for them.

I used to be one of these Chinese who misinterpreted much of ancient China’s

concepts and values, and regarded them as dross. Later, I had the opportunity

to read many ancient Chinese classics with a peaceful, unbiased and non-judgmental

mindset. Then, I realized that I actually knew nothing of ancient Chinese culture.

My prior knowledge of ancient Chinese culture was the twisted version that the

Chinese Communist Party had planted in the minds of the Chinese since it took

over China in the 1949. I realized that the genuine, ancient Chinese culture

was immensely profound. The ancient Chinese culture has been distorted, leading

to the disappearance of many precious Chinese traditions. It has caused the

vast majority of Chinese to lose their understanding of their culture and behave

in ways that are contrary to precious Chinese traditions. As a result, the morals

of China’s contemporary people have continued to deteriorate to a point

where the entire Chinese society is in moral chaos. I hope to clarify some of

the true meaning of these ancient Chinese values and provide people an opportunity

to understand true, ancient Chinese culture.

During the reign of Emperor Chengdi of the Han Dynasty (51 – 7 B.C), there

was a young man named Zhang Fang, whose family had held an official rank for

generations. Zhang Fang’s mother was a princess, and his own wife was the

Empress’ younger sister. Emperor Chengdi and Zhang Fang were bosom friends.

Emperor Chengdi often indulged himself with Zhang Fang in drinking and partying,

often late into the night, and thus neglecting to administer the affairs of

state. Zhang Fang enjoyed Emperor Chengdi’s company, and vice versa. Emperor

Chengdi’s mother, Grand Empress Dowager Wang, felt Zhang Fang was responsible

for Emperor Chengdi’s negligence of duty as emperor. She eventually pressured

Emperor Chengdi to banish Zhang Fang from the capital city. According to historic

records, years later when Emperor Chengdi died in 7 B.C, Zhang Fang couldn’t

stop crying after hearing the news and died soon afterwards.

This is usually considered a trivial, historical episode. What started me thinking

was the comment that an ancient Chinese historian made about Zhang Fang. The

rough translation of the historian’s comment was: “Zhang Fang loved

his emperor dearly, but he was not loyal to him. Because of his love and disloyalty

to the emperor, Zhang Fang was far from [the model of] benevolence and justice.”

Based on today’s modern concepts, Zhang Fang was completely devoted to

Emperor Chengdi, because he was Emperor Chengdi’s most beloved friend in

all kinds of merry-making. In fact, Zhang Fang was such a dear friend that he

died of sorrow over Emperor Chengdi’s death. But the ancient Chinese thought

that Zhang Fang “loved his emperor” but “was not loyal to him.”

They thought Zhang Fang was “far from [the model of] benevolence and justice.”

The historian’s comment led us to consider the ancient Chinese perspective

regarding the meaning of “loyalty to one’s master or emperor.”

This is apparently a completely different perspective than that of today’s

Chinese. For the ancient Chinese, the meaning of true loyalty is an honorable

moral character, far above [the usual concept of] love.

With that in mind, we should probably revisit those most memorable characters

in ancient Chinese history that are known for their undying loyalty. Those loyal

subjects presented brave petitions to their emperors for the benefit of the

people; fulfilled their duties to their deaths; risked their lives to make honest

suggestions to tyrants; bravely stood against those corrupt, high-level officials

that had a very negative influence over the unwise emperors or government administrators.

We already know that the ancient Chinese thought Zhang Fang “loved his

emperor” but “was not loyal to him.” Then the next question is:

what is true loyalty?

Ji An was an important courtier during the reign of Emperor Wudi of the Han

Dynasty (157 – 87 B.C.). Ji An once enraged Emperor Wudi with his frank

suggestions, and many of his colleagues later reproached him, calling him straightforward

and blunt. Ji An explained, “The purpose of having courtiers is to help

the emperor to rule the country. Are we court jesters who are responsible for

pleasing and entertaining the emperor? Is it our job to idly watch the emperor

ruin the country? Are we trusted with the important positions of courtiers only

to put our interest and security before the interest and security of the country?

If so, what will become of this country?”

There was an important discussion related to loyalty in “XV Filial Piety

in Relation to Reproof and Remonstrance” from The Book of Filial

Piety. One of Confucius’ disciples named Zeng asked, “I would

venture to ask if unconditional obedience to the orders of one’s father

can be pronounced filial piety.” Confucius replied, “What words are

these! What words are these! Historically, if the Son of Heaven (an emperor)

had seven ministers who would remonstrate with him, although he did not have

the right methods of government, he would not lose his possession of the kingdom.

If the prince of a state (or a feudal lord) had five such ministers, though

his measures might be equally wrong, he would not lose his state. If a great

officer had three, he would not, in a similar case, lose [the headship of] his

clan. If an inferior officer had a friend who would remonstrate with him, a

good name would not cease to be connected with his character. And the father

who had a son that would remonstrate with him would not fall into the pit of

unrighteous deeds. Where a case of unrighteous conduct is concerned, it stands

to reason that a son must by no means keep from remonstrating with his father,

nor a minister from remonstrating with his ruler. Hence, since remonstrance

is required in the case of unrighteous conduct, how can unconditional obedience

to the orders of a father be accounted as filial piety?”

True loyalty includes helping to prevent one’s master or emperor from

making the wrong decisions. In other words, a subject is loyal when he is responsible

to the country, the people and his emperor. With this in mind, we know that,

by partying without restraint with Emperor Chengdi, Zhang Fang had turned Emperor

Chengdi into a foolish and selfish ruler. Indeed, Zhang Fang could not be further

from being loyal to Emperor Chengdi.

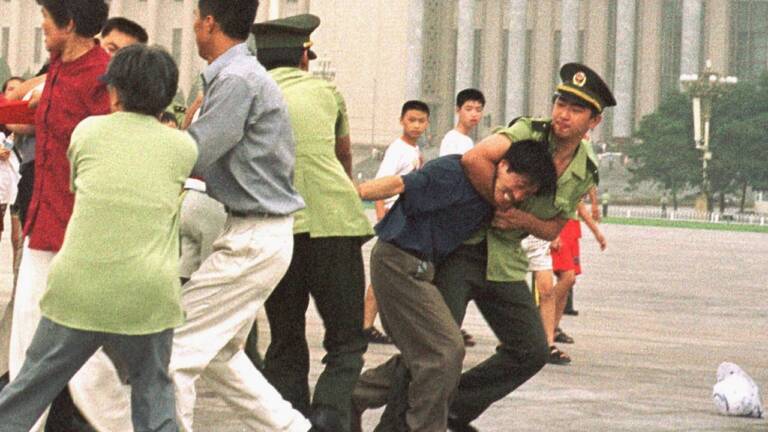

I wonder if there is any “loyal courtier” left in today’s China

who would risk his life to be truly responsible for China and her people. With

the traditional Chinese culture branded in the minds of the ancient Chinese,

they were capable of telling right from wrong. Even during the most chaotic

periods in Chinese history, because of the strong influence of traditional moral

values, the Chinese throughout their history always supported or sympathized

with those truly loyal historic characters, even as they were being persecuted

by others. The public’s support of the loyal subjects was a natural manifestation

of core Chinese moral values. However, since the Chinese Communist Party took

over China, “If a person is not after self-interest, heaven and earth will

kill him” has already become a motto prevalent throughout all of Chinese

society! Apparently, with the erosion of traditional Chinese culture and moral

values, the true spirit of loyalty is fading.

Category: Chinese culture