Catherine Armitage

November 15, 2004

CHINA’S disdain for foreign interference

in its human rights broke through the mask of soft diplomacy one recent Thursday

evening in Canberra.

As a result, 13 members of the Australian media appeared

to have been handed the China scoop of the year.

At a press conference

on annual human rights talks between Australia and China, Chinese assistant foreign

minister Shen Guofang was asked about the 15-year-long house arrest of former

premier of China Zhao Ziyang. He

replied: “There is no problem of so-call

. . . of house arrest. He is free.”

It was an incendiary statement.

Freedom for the 85-year old Zhao could spark the kind of mass uprising which led

to his incarceration in the first place.

Zhao has not been seen in public

since he famously, tearfully, visited the students in Tiananmen Square in May

1989. He was jettisoned soon afterwards by Deng Xiaoping for his soft line on

the protests.

But Shen’s assertion was not true. Life at courtyard No.

6 Fuqiang Hutong where Zhao lives continues as it has for the past 15 years. Armed

police in green uniforms patrol the high grey wall, plain-clothes police hang

around the alley, a bronze banner on the red gate warns: “Closed unit. No

visitors allowed.” The old man needs permission from the highest reaches

of government to step out the gate.

The kindest explanation is

that Shen’s understanding of the word “free” is very different to that

of ordinary Australians. But just maybe, Shen’s assertion was an insult to all

those present, including the Department of Foreign Affairs bureaucrats with whom

he had just spent the day pow-wowing on human rights.

Australia does China

a big favour by corralling its official expressions of concern over China’s horrific

human rights abuses into an annual day-long meeting between bureaucrats behind

closed doors. Since 1997, as a condition of the dialogue, Australia has effectively

agreed not to publicly tackle China on human rights. Especially, Australia no

longer backs resolutions in the UN Human Rights Commission that might lead to

China being “named and shamed”.

Australia won’t openly state,

let alone deplore, the fact that more than 10,000 people a year are executed in

China, often within hours of sentencing, often for economic crimes like stealing

or tax fraud, often after confessions extracted by torture.

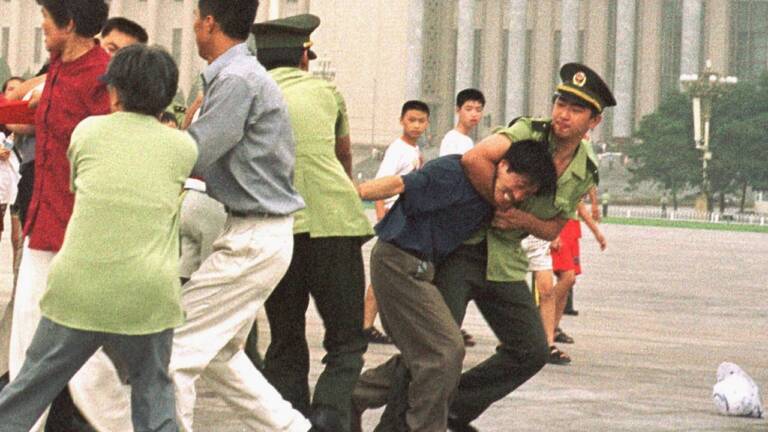

Australia

won’t say in public that Chinese citizens are regularly beaten to death by police

or that more than 100,000 Falun Gong practitioners have been sent to forced labour

camps since 1999, of whom well over 1600 have died of torture or abuse.

Nor

will Australia publicly decry the system of re-education through labour which

imprisoned more than 310,000 people without trial or judicial oversight in 2003

alone, a 50 per cent increase on 2001.

There are 25 billion reasons for

Australia’s circumspection on China’s human rights question. Bilateral trade is

now worth $25 billion a year and growing at an annual rate of 12 per cent.

Australian

ambassador to China Alan Thomas spelled it out at a business dinner in Beijing

last month. He noted how “we are very, very fortunate” to have the raw

materials, agriculture and food products “China wants at the moment”.

He said Australia’s political relationship with China has “no major difficulties

at the moment”. On human rights, “We can raise what are very sensitive,

very prickly issues which China doesn’t like us raising, but we do it in a managed

way,” ambassador Thomas said. “We don’t scream it from the rooftops.

I don’t get up with a microphone in Tiananmen Square, and that is appreciated

[by the Chinese],” he said.

Human rights issues are always raised

when Australian leaders meet the Chinese, diplomats say. Others see this is an

empty gesture. The dialogue isolates and marginalises human rights as a safe arena

that doesn’t extend to other bilateral relations, says Hong Kong-based Nicolas

Becquelin of Human Rights in China.

Privately, diplomats believe that’s

a big part of the reason for “no major difficulties” in the bilateral

relationship. But things could quickly change.

Australians who dread the

prospect of a free trade agreement with China, almost certainly to be negotiated

next year, will no doubt be screaming from the rooftops about human rights –

a prospect in turn dreaded by the Chinese.

And as human rights activists gear

up for an all-out assault on China before the Beijing 2008 Olympics, Australia’s

stance is likely to come under greater international scrutiny.

About a

dozen countries are now signed up for bilateral talks on human rights with China,

including the US, Britain, Canada, Switzerland and Denmark. But even the participating

countries feel a growing sense that they are ineffective, according to a Beijing-based

Western diplomat who is involved.

China is showing its disdain by refusing

to engage in planning the talks, sending along more junior officials, or changing

the days at short notice, as happened with Australia in October, the diplomat

said. The talks are not so much a dialogue as a ritualised reading of set pieces

in which one side lists its concerns and China lists the reasons it won’t act,

according to the diplomat.

Says Becquelin: “I don’t think the dialogues

have ever broken new ground. I have never seen anything useful published as a

result of the dialogues.”

He argues the UN system of binding international

treaties and covenants, some of which are legally binding and many of which China

has signed, is “much much more effective than just bilateral talk shops”.

China sends its best and brightest diplomats to human rights sessions at

the UN, but makes clear its distaste. The UN Human Rights Commission has “low

credibility and efficiency” and is stuck in a Cold War mindset, China’s representative

told a UN session in New York in late October.

In an obvious stab at the

US, China said the commission allows countries which “ignore such large-scale

violations against human rights as foreign military occupation” to “wilfully

name and shame those developing countries they don’t like”.

China

appears to be moving towards cutting down on executions. It has reformed the system

of arbitrary detention of people living or working outside their city of household

registration. Of the 41 cases of incarcerated individuals raised by Australia

in the dialogues since 2001, 15 have been released, including seven out of 25

last year, according to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. “I think

we are making some incremental progress,” said ambassador Thomas.

But

how much improvement can be attributed to the talks is just as debatable as the

assertion that sticking with the UN route would have yielded better results.

John

Kamm is a former head of the American Chamber of Commerce in China who has spent

the past 15 years pursuing individual cases of 900 prisoners in China, of whom

350 have been freed, believes the dialogues are worth pursuing on the basis that

all avenues are worth pursuing. But he, along with Becquelin, believes they are

not used to maximum advantage, not least because dialogue countries don’t co-ordinate

adequately with each other.

Kamm singles out Australia for being overly

secretive and failing to share any lessons or advice, with him or other dialogue

countries. “I can’t recall a single instance in the years I have been doing

this where the Australian government has provided any information to me of any

value, and that is too bad,” he says.

Yet the Australian talks are

seen as among the most useful. They occur with higher-level Chinese officials

than other countries’ talks, and, in a recent breakthrough, the Chinese have invited

non-government organisations to join.

The cynical explanation for this

relative success is that the Australian talks have money tied to them, in the

form of an ongoing aid program on human rights, administered by the Human Rights

and Equal Opportunity Commission, under which Australian experts have provided

training on issues including prison reform, rules of evidence for the judiciary

and domestic violence.

The Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs,

Defence and Trade launched an inquiry into bilateral human rights dialogues after

an article in The Australian questioned the value of the Chinese talks last year.

The 12 submissions so far are almost uniformly critical of the China dialogue

for its secrecy, lack of accountability and lack of outcomes.

Ann Kent

of the Australian National University Centre for International and Public Law,

a world authority on human rights mechanisms, blasted the annual dialogues for

actively undermining both well-established UN monitoring mechanisms and Australian

values.

“Every year Australia approaches the bilateral dialogue with

its hands already tied behind its back. It has no bargaining power. It is able

neither to invoke the possibility of international disapproval nor to apply sufficient

Australian pressure, for fear of destabilising the relationship,”

according

to Kent. The sole virtue of the dialogue, the aid program, should be detached

from the talks because it lends legitimacy to an essentially empty process, Kent

argues.

© The Australian

http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/common/story_page/0,5744,11385213%255E28737,00.html

1. Jiang Regime’s slanderous words omitted.

Posting date: 15/Nov/2004

Original article date: 15/Nov/2004

Category:

Media Report