Rosemary Neill meets Jennifer Zeng, AUTHOR

SHE can talk about

the brainwashing and torture she endured, and maintain her composure. She can

tell you, without breaking down, about her husband being arrested and detained.

But the tears spill out, unbidden and bitter, when Jennifer Zeng discusses how

the Chinese Government tried to turn her only child against her because she practises

Falun Gong. This is the meditation-based spiritual movement banned by the Communist

Party in one of its harshest crackdowns since the Cultural Revolution. The party

maintains Falun Gong is an evil cult.

“There was a stage when my daughter

become so confused,” Zeng says. “She was so scared and confused. She

was only six or seven. She had to make a choice between her own mother and what

the party told her.”

Today, 12-year-old Shitan lives in Sydney with

her mother, a soft-skinned, soft-spoken woman of 38. Zeng fled China and came

to Australia as a refugee in 2001, and her daughter followed. “I’m very happy

now that she is in Australia,” says Zeng, adding that Shitan would love to

see her father, grandfather and friends in Beijing.

But the schoolgirl

knows she can’t visit, as it is likely her mother would be arrested. For while

she leads an ostensibly quiet life in the suburbs, working for a lifestyle magazine

and meditating, Zeng continues her struggle against China’s persecution of those

who practise Falun Gong.

Next week, Zeng’s account of her ordeal, Witnessing

History: One Woman’s Fight for Freedom and Falun Gong (Allen & Unwin, $29.95),

will be released in Australia. It is the first book by a Falun Gong follower who

has suffered imprisonment and torture — and it has been black-listed in China.

In it, Zeng explains how her life was “thoroughly transformed” after

she discovered Falun Gong. A scientist by training, she had suffered two haemorrhages

after giving birth. She contracted hepatitis C from blood transfusions and was

unable to work or care for Shitan. “I was only 30 years old; I had a wonderful

husband and a precious daughter but I felt so wretched that life hardly seemed

worth living,” she writes. But once she started practising Falun Gong, which

combines meditative exercises with Taoist and Buddhist precepts, she regained

her health, career and optimism. Indeed, she felt she was leading a “different

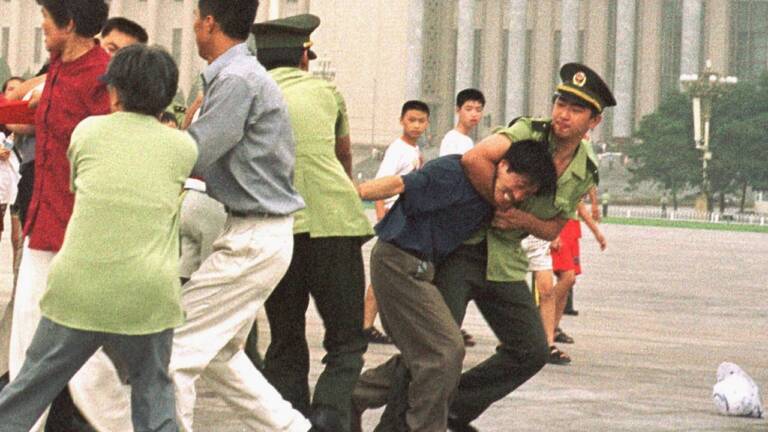

existence”. But her happiness was short-lived. In 1999, the Communist Party

banned Falun Gong after 10,000 followers protested in Beijing against the mistreatment

of Falun Gong members in another city. This was the boldest challenge to the party’s

power since the Tiananmen Square student demonstrations of 1989.

Zeng refused

to give up practising, even after she was arrested three times. In 2000, she was

sent to a labour camp. There, she had to squat in the sun all day and was subjected

to electric shocks and brainwashing sessions. The aim was to have her renounce

her spiritual beliefs. To add to the humiliation, “reformed” inmates

were forced to help re-educate or beat up other Falun Gong followers. Zeng couldn’t

bring herself to do this.

She spent 10 months in the labour camp before

“reforming”; at times she says she felt on the verge of total collapse.

“I witnessed somebody else become totally insane and I couldn’t guarantee

I wouldn’t end up in the same situation. That was really, really frightening,”

she says, her voice fading to a whisper.

Her commitment to her faith can

seem extraordinarily courageous and zealous. To get out of the labour camp, she

gave interrogators the false impression she had recanted. She castigates herself

for this, writing that she failed “the standards required of a Falun Gong

student”. But what was the alternative? Going mad or dying behind high wire

fences? “Possibly,” she concedes reluctantly.

Not all of her

family supported her single-minded pursuit of her beliefs. Her terrified mother-in-law

tried to stop her leaving the family’s Beijing flat to meditate outdoors.

In

2002, Zeng was one of seven followers who filed charges with the UN against former

Chinese president Jiang Zemin for persecuting Falun Gong practitioners. Then living

here, she received threatening international phone calls from distant relatives.

“I understood their reaction,” she says. “In their eyes

it’s so shocking an action to take and so dangerous, to put my husband in this

kind of situation. I understand their anger. I always felt for people who live

under terror.” Four days after the charges were filed, Zeng’s husband was

arrested and her daughter spent her 10th birthday alone. “[I was] thrown

into greater torment than when I was thrown into prison myself,” she says.

Her husband, who hopes to join her in Australia, was held for a month and is still

under surveillance. Soon after, his mother contracted cancer and died. Zeng believes

she became sick “from the shock”.

Will her book put her husband

at further risk? She thinks that, paradoxically, the more her story is exposed,

the safer her husband will be. “They [the Chinese authorities] wouldn’t want

to advertise my book by arresting him,” she explains. To this day, it’s unsafe

for her to talk freely to her family in China. The communist authorities know

everything she’s doing here, she says.

“My main concern is not to

bring trouble to others. Maybe some little action of mine could result in big,

big trouble for someone inside China,” she says. Aware of this risk, her

mother has forbidden contact between Zeng and her sister, who has spent 18 months

in a labour camp because of her Falun Gong beliefs.

Has the toll on her

family been worth it? Zeng says her family is innocent and that she blames their

suffering on her persecutors rather than her faith: “I don’t believe that

persecution is right … the law should deal with people’s actions and deeds only

but in China it is used to deal with your thoughts.”

She is dismayed

that many in Australia’s Chinese community have bought the Communist Party line

that Falun Gong is an evil cult. (The local Falun Gong branch is officially excluded

from Sydney’s Chinese New Year parade.) And Western experts seem unsure whether

Falun Gong is a benign faith or a more sinister sect. But they don’t doubt that

its practitioners are persecuted in China — largely because the movement has

spread at an astonishing speed since it was founded in 1992. Today, it claims

tens of millions of followers in and outside China.

Falun Gong’s leader, Li

Hongzhi, is a former grains clerk and trumpet player from northeast China who

moved to New York in 1998. The Chinese Government says he is a charlatan who changed

his birthday to May 13 — the same as Buddhism’s founder. Li denies this.

Nevertheless,

some followers refer to him as Living Buddha. Li believes in aliens and has told

Time magazine he exists at “a higher level”. According to the BBC, the

communists blame him for the deaths of thousands of devotees, claiming he has

stopped them seeking medical help. Li says this is untrue.

Zeng says Falun

Gong has spread so quickly simply “because it is so good”; the positive

effects on followers’ physical and mental health are “so obvious”. She

says she wrote her book to “expose the evil” of China’s labour camps

and to highlight the plight of other Falun Gong inmates: “What we ask is

for an end to the persecution and for the freedom to practise our own beliefs.

I regard that as basic human rights — it’s not political at all.”

Posting

date: 3/Mar/2005

Original article date: 27/Feb/2005

Category: Media Report