Introduction

Since the commercialisation of the Internet in China in 1995, China has

become one of the fastest-growing Internet markets in the world. The number

of domestic Internet users is doubling every six months.

With the introduction of the Internet, news reaches China from a

multiplicity of sources enabling people to form opinions, analyse and share

information and to communicate in ways previously unknown in China. Lively

on-line debate characterised the start of the Internet in China. However,

the potential of the Internet to spread new ideas has led the authorities to

take measures to control its use.

The authorities have introduced scores of regulations, closed Internet

cafes, blocked e-mails, search engines, foreign news and

politically-sensitive websites, and have recently introduced a filtering

system for web searches on a list of prohibited key words and terms.

Those violating the laws and regulations which aim to restrict free

expression of opinion and circulation of information through the Internet

may face imprisonment and according to recent regulations some could even be

sentenced to death. Amnesty International has compiled records of 33

prisoners of conscience who have been detained for using the Internet to

circulate or download information. These cases are listed in the appendix to

this document and some are described in more detail in a separate document

entitled, State Control of the Internet: Appeal Cases, November 2002, AI

Index: ASA 17/046/2002.

The Internet in China – Facts and Figures

China joined the global internet in 1994. It became commercially available

in 1995.In June 2002 the number of internet users had reached 45.8 million –

an increase of 72.8% over twelve months as compared to figures released in

2001. Over 16 million computers are now linked to the Internet, an increase

of 61 per cent in one year. The number of websites has reached 293,213,

representing almost a 21 per cent increase over the same period.

(1) Some

private surveys put the current number of users at above 50 million, making

China second only to the United States in the number of Internet

users.

(2)China’s Internet market is likely to become the largest in the

world within four years.

(3) More than 40% of internet users are based in

prosperous cities, particularly Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and

Guangzhou.

(4)Internet users are predominantly young, with almost 40% aged 24

or under

(5).The proportion of female users continues to increase and now

represents over 39 per cent of all users.Initially, Internet users were

predominantly those with a high school or college education. But those

without college education now make up 68.3% of the total indicating a

broader spectrum of use within China.

(6) Officials at the Asia-Pacific

Economic Conference (APEC) in February 2001 predicted that 70 per cent of

Chinese foreign trade companies will be able to conduct import and export

business via electronic means by the year 2005

(7).Since 1995 more than 60

rules and regulations have been introduced covering the use of the

Internet.In January 2001, a new regulation made it a capital crime to

“provide state secrets” to organizations and individuals over the

Internet.30,000 state security personnel are reportedly monitoring websites,

chat rooms and private e-mail messages.Thousands of Internet cafes

throughout China have been forced to close in recent months. Those that

remain are obliged to install software which filters out more than 500,000

banned sites with pornographic or “subversive” elements.

On 26 March 2002,

the authorities introduced a voluntary pledge, entitled, A Public Pledge on

Self-Discipline for the China Internet Industry, to reinforce existing

regulations controlling the use of the Internet in China. Over 300 Chinese

Internet business users have reportedly signed the public pledge, including

the US-based search engine, Yahoo!In July 2002, a Declaration of Internet

Users’ Rights was signed and published by 18 dissidents calling for complete

freedom for Chinese people to surf the Internet.

Political Dissidents and Others Imprisoned for Using the Internet

The Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right

includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive

and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of

frontiers.

Article 19, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Many are imprisoned in

China solely for peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression

and opinion, in violation of international standards. They include people

who have expressed their views or circulated information via the Internet or

email.

The Internet, e-mail and Bulletin Board Services (BBS) have been used by

dissidents, Falun Gong practitioners, Tibetan exiles and others to circulate

information or protest against repression, publicise their cause or to draw

support for online petitions and open letters. E-mail and the Internet have

also provided a means of communication within China and with the Chinese

dissident community abroad. In December 1999 Wang Youcai, founder of the

China Democracy Party (CDP), was sentenced to 11 years’ imprisonment for

subversion. Two of the accusations against Wang Youcai involved sending

e-mail to Chinese dissidents abroad and accepting overseas funds to buy a

computer. Lin Hai, a computer engineer from Shanghai, was arrested in March

1998 and is considered to be the first person to have been sentenced for the

use of the Internet in China. He was accused of providing 30,000 email

addresses to VIP Reference, a US-based on line pro-democracy magazine, and

charged with subversion and sentenced to two years in prison in June

1999.Huang Qi was arrested in June 2000 after he had set up his own website,

www.6-4tianweg.com which called for political reforms, and helped dissidents

trace missing relatives following the crackdown on the 1989 pro-democracy

protests. Huang Qi was charged with subversion and tried in secret in August

2001. Over two and a half years after his arrest Huang Qi is still detained

without a verdict having been announced. For more details see, State Control

of the Internet in China: Appeal Cases, AI Index: ASA 17/046/2002.

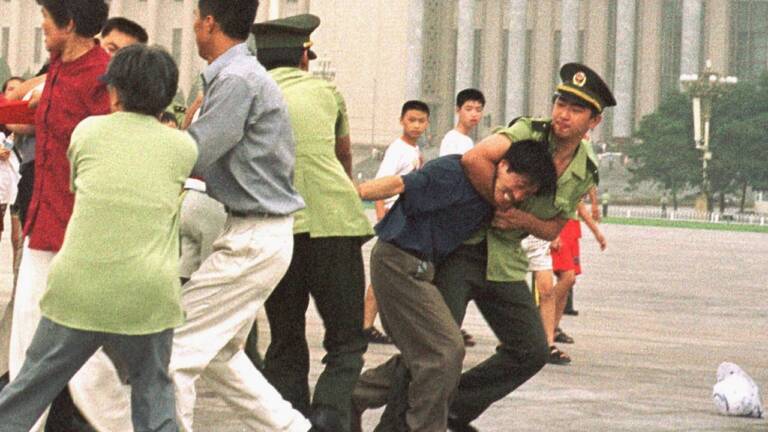

Members

of the Falun Gong spiritual movement, banned in July 1999 as a ‘heretical

organization’, have used the Internet and e-mail to circulate information

about repression against the group. Some have been arrested as a result. The

Chinese authorities have now shut down the group’s websites and blocked

overseas websites. At least 14 Falun Gong practitioners have been detained

and imprisoned for Internet-related offences, several have died in custody

reportedly as a result of torture. See State Control of the Internet in

China, Appeal Cases, AI Index: ASA 17/046/2002, November 2002.

Amnesty International has investigated the cases of 33 people believed to be

prisoners of conscience. They have been detained or are serving long

sentences in prison or labour camps for Internet-related offences. Three

have died in custody, two of whom reportedly died as a result of torture,

and there are reports that others have been tortured or ill-treated in

detention.

Those tried are reported to have been denied fair trial, in violation of

international standards for fair trial. Many trials were held in secret. Six

of those tried are still waiting for the verdict to be announced. Sentences

against others range from two to eleven years. Those detained include 14

members of the Falun Gong spiritual movement, four members of the China

Democracy Party, and other political dissidents. They come from Beijing and

a variety of provinces in China.

All were peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression and

opinion. The accusations against them include circulating and downloading

articles calling for political and social reform, greater democracy and

accountability or redress for abuses of human rights. Most have been charged

with “subversion” or membership of a “heretical organization”. This latter

charge has been used widely against Falun Gong practitioners and members of

other Qigong or religious groups banned by the authorities. See appendix at

the end of this document and the separate document entitled, State Control

of the Internet: Appeal Cases, November 2002, AI Index: ASA 17/046/2002.

Rules and Regulations(8)

“… Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall

include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all

kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print…or

through any other media of his choice”. Article 19 of the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, signed by China in 1998 The

provisions set out in the Chinese Criminal Law(9) and the recent regulations

provide the authorities with the means to monitor and control the flow of

information on the Internet, keep track of users, enforce responsibilities

on operators and police, and punish those that violate provisions affecting

the Internet.

Scores of administrative regulations governing telecommunications and the

Internet have been introduced since 1994. Many update or reinforce earlier

regulations as the perceived threats and challenges to the authorities of

the Internet grow or change.

Many of these regulations, particularly those concerning “state secrets”,

are broad and ill-defined. Their implementation has often been harsh,

resulting in arbitrary arrest, imprisonment, sometimes torture, confiscation

of equipment and heavy fines. Since January 2001, those who provide “state

secrets” over the Internet to overseas organizations and individuals may be

sentenced to death.

Regulations affecting the Internet have been issued by different Ministries

within the State Council (the executive arm of central government), and as

the responsibility for implementation has widened, many basic provisions of

earlier regulations have been reinforced at different levels. New

organizations have also been set up to control the use of the Internet,

including the State Council’s Internet Propaganda Administrative Bureau,

which guides and monitors the content of Chinese websites, and the Ministry

of Public Security Computer, Monitoring and Supervision Bureau.

The following is a brief description of key laws and regulations introduced

since 1994:

1994

The State Council issued the “Safety and Protection Regulations for Computer

Information Systems”(10). These regulations gave the Ministry of Public

Security (MPS) overall responsibility for “policing” the Internet “to

supervise, inspect and guide the security protection work; investigate and

prosecute illegal criminal cases ;and perform other supervising duties”.

1997

The Ministry of Public Security issued some far-reaching regulations,

“Computer Information Network and Internet Security, Protection and

Management Regulations”(11) which were approved by the State Council in

December 1997 and elaborated on in more recent regulations.

Under these regulations, all Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and other

enterprises accessing the Internet are responsible to the Public Security

Bureau. Internet companies are required to provide monthly reports on the

number of users, page views and user profiles. Internet Service Providers

are also required to assist the Public Security Bureau in investigating

violations of the laws and regulations. Serious violations of the

regulations will result in the cancellation of the ISP licence and network

registration. As a result some ISPs have introduced self-censoring policies

to deal with the implementation of these 1997 regulations, including

volunteers, who patrol chat rooms and bulletin boards to ensure observance

of the regulations.

2000

On 25 January the Bureau for the Protection of State Secrets issued the

“State Secrets Protection Regulations for Computer Information Systems on

the Internet”(12). These regulations prohibit the release, discussion or

dissemination of “state secrets” over the Internet. This also applies to

individuals and units when making use of electronic bulletin boards and chat

rooms. Operators are under an obligation to report “harmful” content to the

local Public Security Bureau. All journalists and writers are required to

check their written texts with the state-controlled media before

publication.

Amnesty International is concerned that laws and regulations on “state

secrets” have been used in the past to imprison people exercising peacefully

their fundamental rights to freedom of expression and that the prohibition

of “state secrets” in the Internet regulations is yet another way of

limiting freedom of expression.

Tough new Measures for Managing Internet Information Services(13) were

issued in September 2000 by the State Council. “The Measures for Managing

Internet Information Services” regulate the Internet services and promote

the “healthy” development of these services. They also stipulate that all

Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and Internet Content Providers have to

keep records of all subscribers’ access to the Internet, account numbers,

the addresses or domain names of the websites and telephone numbers used.

ISPs are also required to maintain users’ records for 60 days and to provide

these to “the relevant state authorities” when required.

These measures draw upon the much broader Telecommunications Regulations of

the People’s Republic of China(14) also issued in September 2000 by the

State Council.

Article 15 of these Measures describes information that is prohibited:

(1) Information that goes against the basic principles set in the

Constitution;

(2) Information that endangers national security, divulges state secrets,

subverts the government, or undermines national unification;

(3) Information that is detrimental to the honour and interests of the

state;

(4) Information that instigates ethnic hatred or ethnic discrimination, or

that undermines national unity;

(5) Information that undermines the state’s policy for religions, or that

propagates heretical organizations or feudalistic and superstitious beliefs;

(6) Information that disseminates rumours, disturbs social order, or

undermines social stability;

(7) Information that disseminates pornography and other salacious materials;

that promotes gambling, violence, homicide, and terror; or that instigates

the commission of crimes;

(8) Information that insults or slanders other people, or that infringes

upon other people’s legitimate rights and interests; and

(9) Other information prohibited by the law or administrative regulations.

Amnesty International is concerned that the range of information prohibited

by this regulation allows the authorities to restrict freedom of expression

over the Internet in a broad and sweeping manner which goes far beyond what

would be regarded as legitimate restrictions under international standards.

As part of the ongoing effort to control access to information available on

the Internet, new regulations were introduced by the Ministry of Information

Industry and the Information Office of the State Council on 7 November

2000(15). These regulations place restrictions on foreign news and the

content of online chat rooms and bulletin boards.

According to these regulations, the State Council’s Information Office will

supervise websites and commercial web portals such as Sohu.com and Sina.com

and media organizations may only publish information which has been subject

to controls in line with the official state media.

On 28 December 2000 The Decisions of the NPC Standing Committee on

Safeguarding Internet Safety(16) were introduced. Under these regulations

those spreading rumours, engaging in defamation or publishing “harmful”

information, inciting the overthrow of the government or division of the

country on the Internet will now be punished according to the law. Prison

sentences can be passed against those who promote ‘heretical organizations’

and leak “state secrets”.

2001 – The Death Penalty for Offences Related to Use of the Internet

On 21 January, the Supreme People’s Court ruled that those who cause

“especially serious harm” by providing “state secrets” to overseas

organizations and individuals over the Internet may be sentenced to death:

“Those who illegally provide state secrets or intelligence for units,

organizations and individuals outside the country through Internet with

serious consequences will be punished according to stipulations of the

Criminal Law; in especially serious cases, those who steal, make secret

inquiries or buy state secrets and intelligence and illegally provide

gathered state secrets and intelligence to units outside the country will be

sentenced to ten or more years of fixed-term imprisonment or imprisonment

for life and their properties may concurrently be confiscated by the state.

In cases of a gross violation of law and where especially serious harm is

caused to the state and people, law offenders may be sentenced to death and

their properties will be confiscated by the state.”(17)

This ruling was believed to be a reaction to the revelations contained in

The Tiananmen Papers (18) released in the United States. Extracts of these

papers were translated and posted on the Internet.

2002

In January, the Ministry of Information Industry (MII) announced new

regulations(19) that require Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to monitor

more closely peoples’ use of the Internet. Software should be installed to

ensure that messages are recorded and if they violate the law the ISP must

send a copy to the Ministry of Information Industry, the Ministry of Public

Security and the Bureau for the Protection of State Secrets.

Tough new regulations introduced by the Ministry of Culture restricting

access to the Internet and the operations of Internet cafes entered into

force on 15 November 2002.(20). Proprietors of Internet cafes are obliged to

install software preventing users from accessing information considered

“harmful to state security”, as well as disseminating, downloading, copying

or browsing material on “heretical organizations” , violence and

pornography. Those aged under 18 years old are banned from Internet cafes.

Operating licences may be withdrawn and fines imposed if these regulations

are not properly implemented, (for further information, see the section on

Closure of Internet Cafes).

Implementing the Restrictions: The Blocking and Filtering of Websites

Bulletin Boards and Search Engines

The Internet is a popular and powerful channel for the government and

ordinary Chinese to hear each other and to be heard. However, the controls

placed on operators and users of the Internet have increased greatly in

recent years. This has taken the form of censorship and penalties against

all those involved with bulletin boards, chat rooms, e-mail and search

engines who contravene the provisions of the Criminal Law and the scores of

regulations.

Blocking

The authorities routinely block news sites, especially foreign-based sites,

including those featuring dissident views or banned groups. The blocking

appears to be intermittent but more prevalent at times of heightened

security such as the anniversary of the crackdown on the 1989 pro-democracy

protests, the annual meeting of the National Party Congress or visits from

heads of state or government.

Many websites, considered to contain politically sensitive information, such

as those of human rights organizations and banned groups as well as

international news sites, are all inaccessible from China. The average

Internet user in China knows there are certain sites that are inaccessible,

searches that cannot be done or content that cannot be looked at.

In late August 2002, the popular search engine, Google.com, could no longer

be accessed from China for several weeks. Altavista.com was also reportedly

blocked. Protest messages were registered on bulletin boards throughout

China.

Filtering

In mid-September 2002, China introduced new filtering systems based on key

words, regardless of site or context. Filtering software has reportedly been

installed on the four main public access networks in China. Prohibited words

or strings of words on websites, e-mail, foreign news sites and search

engines are affected. Users trying to access information which includes key

words such as ‘human rights’, ‘Taiwan’, ‘Tiananmen’, ‘Falun Gong’ and

‘Tibet’ are blocked and browsers indicate that the “page cannot be

displayed”. The New Culture Forum site (www.xinwenming.net), the first

China-based web site started by veteran democracy activists, was closed down

after four months, on 3 August 2000, by state security officials for posting

“reactionary materials” on its website. The main aim of the New Culture

Forum was to spread the message that Chinese politics should adopt

compromise and conciliation to enable democratic change. The Forum was run

by a group of dissidents from Shandong province. Xin Wenming, the site’s

webmaster, issued a statement in response to the shutdown, denouncing the

government’s suppression of freedom of expression on the Internet and

calling for the end to the nationwide crackdown on websites that engage in

political criticism.

However such groups and individuals in China have used a variety of means to

overcome Internet censorship including the use of proxy servers(21) situated

outside of China, to circumvent firewalls(22) and the blocking of websites.

The Closure of Internet Cafes

Following a fire at Lanjisu Internet café in Beijing in June 2002 which

killed 25 people, the Public Security Ministry announced that it had closed

down 2,400 Internet cafes in Beijing for safety reasons. Officials in other

cities such as Shanghai and Tianjin took similar action. Since then the

authorities have introduced a range of regulations affecting Internet cafes,

instituted government checks and ordered filtering software to be installed.

While Amnesty International recognizes the importance of health and safety

regulations for all public services including internet cafes, the

organization is concerned that the fire at the Internet café in Beijing may

have been used as a pretext to crackdown still further on freedom of

expression in China.

According to a recent statement issued by the Minister of Culture(23), there

are 200,000 Internet cafes throughout China but only about 110,000 of them

are officially registered. All Internet café owners have been obliged this

year to re-register with a number of different authorities to obtain a

licence and avoid being shut down or fined heavily.

Several weeks after the Beijing Internet café fire, the government ordered

all Internet cafes to augment their filtering software within weeks and to

keep records of all users for a 90-day period. The software prevents access

to 500,000 foreign websites, such as foreign newspapers, Falun Gong

websites, websites on democracy and human rights and others which are

considered “reactionary” or are “politically-sensitive”. Those attempting to

access these banned sites are automatically reported to the Public Security

Bureau. Internet police in cities such as Xi’an and Chongqing can reportedly

trace the activities of the users without their knowledge and monitor their

online activities by various technical means.

Public Pledge on Self-Discipline for China Internet Industry

In addition to enforcing controls directly, the Chinese authorities are

using a variety of means to force Internet companies to take greater

responsibility for implementing the numerous laws and regulations

controlling the use of the Internet in China. In March 2002, the Internet

Society of China(24) issued The Public Pledge on Self-Discipline which

entered into force in August 2002.

Signatories to the Pledge agree to:

“…..refrain from producing, posting or disseminating pernicious

information that may jeopardise state security and disrupt social stability,

contravene laws and regulations and spread superstition and obscenity.”

Those concerned with the restrictions placed by the authorities on freedom

of expression in China regard the Pledge as another means of censoring

certain types of information disseminated on the Internet which is deemed to

be politically-sensitive.

In July 2002 the Pledge had been signed by over 300 signatories including

the US-based search engine Yahoo!. A lawyer working at Yahoo! reportedly

stated that Yahoo! will conform to local laws in countries where it

operates(25).

While Amnesty International (AI) recognizes that Internet companies should

be regulated and that restrictions on their activities may be legitimate, AI

is concerned at the wide-ranging and broadly defined nature of this Pledge.

The organization fears that this new instrument will be used as part of

wider attempts to restrict the freedom of expression and association of

Internet users in China.

Internet Freedom and Corporate Responsibility

“The Internet is helping Chinese people open their minds to the whole

world”. Ruby Yu, Chief Operating Officer, Zhaodaola.com, a Chinese

commercial website The rapid rise of the Internet has been greatly aided by

the involvement of foreign companies in China. Foreign telecommunications,

software and hardware companies are investing heavily in the development of

China’s Internet.

Amnesty International is concerned at reports that some foreign companies

may be providing China with technology which is used to restrict fundamental

freedoms.

Sohu.com, a Chinese Internet portal, reportedly funded by overseas

companies, and financed by leading investment banks and other venture

capital firms from the West, reminds those accessing its chat room that

“topics which damage the reputation of the state” are forbidden. “If you are

a Chinese national and willingly choose to break these laws, Sohu.com is

legally obliged to report you to the Public Security Bureau”.

In November 2000, the Ministry of Public Security launched its “Golden

Shield”(26) project. This project aims to use advanced information and

communication technology to strengthen police control in China and a massive

surveillance database system will reportedly provide access to records of

every citizen. To realise this initiative, China depends on the

technological expertise and investment of foreign companies.

Foreign companies, including Websense and Sun Microsystems, Cisco Systems,

Nortel Networks, Microsoft,(27) have reportedly provided important

technology which helps the Chinese authorities censor the Internet. Nortel

Networks(28) along with some other international firms are reported to be

providing China with the technology which will help it shift from filtering

content at the international gateway level to filtering content of

individual computers, in homes, Internet cafes, universities and businesses.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights calls on “every individual and

every organ of society” to play its part in securing human rights for all.

Amnesty International believes that multinational companies operating in

China have a responsibility to contribute to the promotion and protection of

fundamental human rights.

Declaration of Citizens’ Rights for the Internet

In protest against the measures taken by the authorities to control freedom

of expression and freedom of information and association on the Internet, a

group of 18 dissidents and intellectuals published a Declaration of

Citizens’ Rights for the Internet on 29 July 2002.

This Declaration challenges the regulations introduced by the authorities

and urges the National People’s Congress and international human rights

organizations to examine the constitutionality and legitimacy of certain

regulations. By October 2002 the Declaration had the support of over 1000

web publishers and Internet users.

The Declaration(29) cites the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and states that,

“……a modern government should be based on the right of individual

freedom of speech, the right of organizing associations, the right of

questioning government decisions and the right of openly criticizing the

government.

….A modern society should be an open society. At the historical juncture

of the Chinese nation once again transforming itself from a traditional

society to a modern society, any blockade measures are all unfavourable to

China’s society joining paths with the world and the peace and progress of

China’s society.

…..Every citizen and government should undertake its responsibility and it

has become extremely urgent to safeguard Internet freedom.”

One of its signatories, Wan Yanhai, a doctor and web site publisher, was

detained on 25 August 2002 on suspicion of “leaking state secrets” and

released on 20 September 2002 following international campaigning on his

behalf by human rights organizations. He was arrested in connection with

publishing a document on the internet detailing deaths from AIDS in Henan

Province as a result of selling blood to government-sanctioned blood

collectors.

Wan Yanhai worked at the AIDS Action Project, a Beijing-based education and

activism group, whose offices were closed by the authorities in June 2002.

The web site, (www.aizhi.org) an important independent source of information

about the HIV/AIDS crisis in China, had promoted the rights of farmers in

Henan Province who had contracted AIDS from selling blood.

On 1 August 2002, Wan Yanhai had circulated an online appeal to all

independent Web publishers asking them to join him in protesting against new

regulations by giving themselves up to the authorities for operating

“illegal” websites(30). Wan Yanhai had also reportedly made use of Internet

chat rooms, discussion and e-mail groups in his efforts to publicise his

cause and promote freedom of opinion and expression in China.

Conclusion

The Internet – A Force for Change in China? “China is not turning back….It

[the Internet] means more social justice, more discussion, more

transparency,…..The whole thing will turn China into a much more

democratic society” Charles Zhang, Chief Executive,

Sohu.com, a Chinese commercial website The Chinese authorities have

introduced scores of regulations to restrict freedom of expression over the

Internet and have taken a variety of measures to control and restrict its

use. They have also detained or imprisoned people who circulated

“politically sensitive” information over the Internet, some of whom are

serving long sentences in prison. Amnesty International is calling for their

release and for a review of regulations and other measures in China which

restrict freedom of expression in a manner going far beyond what would be

regarded as legitimate restrictions under international standards.

Despite the measures introduced by the authorities to stifle freedom of

expression over the Internet, the new technology is a cornerstone for

economic growth in a country with over a fifth of the world’s population. As

the importance of the Internet grows so too will the millions of users and

the demands of those seeking justice and respect for human rights in China.

List of People Detained for Internet-related Offences in China

(1) The China Internet Network Information Centre, (CINIC), a report issued

in June 2002

(2) Nielson/NetRatings (a private US online rating service)

(3) Ibid

(4) Ibid

(5) Ibid

(6) Ibid

(7) The China Daily

(8) This paper only describes some of the key regulations affecting freedom

of expression, opinion and information.

(9) The Criminal Law of China, adopted in July 1979 and amended in 1997.

(10) Regulations for the Safety Protection of Computer Information Systems

(Zhonghua renmin gongheguo jisuanji xitong anquan baohu tiali, Fazhi Ribao

(Legal Daily) February 1994 issued by State Council Order no. 147, signed by

Premier Li Peng on 18 February 1994 and RAND report, You’ve Got Dissent,

dated 26 August 2002, www.rand/org/hotpress.02/dissent.html.

(11) Freedom of expression and the Internet in China, September 2002,

www.hrw.org/backgrounder/asia/china-bck-0701.htm

(12) State Secrets Protection Regulations for Computer Information Systems

on the Internet (Jjisuanji xinxi xitong guoji lianwang baomi guanli guiding)

(13) Digital Freedom Network, 28 October 2002,

(14) China’s ruling body considers bill to control Internet access, Xinhua

news agency, Beijing, 20 September 2000

(15) RAND Report, You’ve got Dissent, 26 August 2002, www-rand/org/hot/pr

ess.02/dissent.html

(16) China Legal Change: Summary Archives,

(17) “China: Supreme People’s Court on Stealing State Secrets”, Xinhua News

Agency, 21 January 2001, BBC Monitoring, 23 January 2001.

(18) The Tiananmen Papers were compiled from secret documents describing how

the authorities dealt with the crushing of the pro-democracy protests in

1989. The Tiananmen Papers by Zhang Liang, Perry Link and Andrew J. Nathan;

Little, Brown & Company, January 2001

(19) Digital Freedom Network, 28 October 2002,

(20) Xinhua, Beijing, 15 October 2002 and China passes tough new regulations

on Internet access and cafes, AFP, 11 October 2002.

(21) A proxy server is a server that acts as an intermediary between a user

and the Internet to ensure security, administrative control and caching

service. Proxy servers are used to improve the performance in accessing web

pages or to filter request to specific websites or content. For more

information, see www.webopedia.com

(22) A firewall is a system designed to prevent unauthorized access to or

from a private computer network. For further information, see

www.webopedia.com

(23) China Tightens Control of Internet Cafes, Xinhua, Beijing, 15 October

2002.

(24) An organization acting as the main professional association for the

Internet Industry in China

(25) Yahoo! Yields to Chinese Web laws, CNET News.com, dated 14 August 2002,

(26) China’s Golden Shield, by Greg Walton, China Rights Forum, No, 1. 2002.

(27) Multinationals making a mint from China’s Great Firewall, by David Lee,

South China Morning Post, 2 October 2002.

(28) China’s Golden Shield by Greg Walton, Rights and Democracy,

www.ichrdd.ca/english/commdoc/publications/globalization/goldenShieldEng.

html

(29) For the full text, see Chinese Scholars Issue Declaration on Rights of

Internet Users, 29 July 2002, BBC Monitoring and the Information Centre for

Human Rights and Democracy.

(30) The Great Firewall of China, by Xiao Qiang and Sophie Beach, August 25,

2002, www.latimes.com/technology/la-op-beach25aug25.story

Amnesty International is impartial and independent of any government,

political persuasion or religious creed.

http://cgi.wn.com/?action=display&article=16993123&template=worldnews/sea

rch.txt&index=recent

Posting date: 28/Nov/2002

Original article date: 27/Nov/2002

Category: World News