by Lawrence K. Altman

While the World Health Organization is encouraged by the declining number of

SARS cases around the world, the agency cautions that there are many

imponderables about the disease, particularly the reliability of information

from China, where the disease has struck hardest.

A major concern is the viral disease’s volatility. SARS, or severe acute

respiratory syndrome, first erupted in Guangdong Province in China last

November. Since then, SARS has been reported in more than 30 countries with

unequal force. The United States and most other affected countries have

prevented imported cases from spreading to other people. But across the

border, in Toronto, SARS has hit with devastating force. In many areas, SARS

has disrupted health care systems. Doctors and nurses have died from the

disease. Beyond the personal tragedies the illness has caused, SARS has

disrupted care in emergency rooms, hospitals and offices, postponing surgery

and other treatments for many people with other conditions.

Initially, health officials feared the worst from SARS a global epidemic

that could rival the 1918-19 influenza pandemic. Now, many health officials

say that scenario appears unlikely, that SARS may have peaked, and express

confidence that SARS can be contained.

Still, officials are urging great vigilance. “SARS has entered a time of

great danger” because people tend to become overconfident and lower their

guard when outbreaks wane, said Dr. David Heymann, the WHO’s executive

director for communicable diseases.

Missing a single case can fire up a new outbreak, as happened in Toronto.

Further, many questions about SARS remains unanswered, including how

important animals are in its transmission, whether it has a seasonal pattern

and whether it will return in stronger form next year.

The answers will take “considerable research and at least a year,” Heymann

said in a telephone interview from Geneva.

The World Health Organization, which is part of the United Nations, is

responsible for the global response to SARS and has been seeking clues as to

whether the virus has weakened and become less virulent as it has passed

from person to person. Such a change might account for the recent drop in

the number of new cases. But the agency says it doubts that theory.

“The disease appears to be very hard and very, very strong in maintaining

its virulence” in humans, Heymann said.

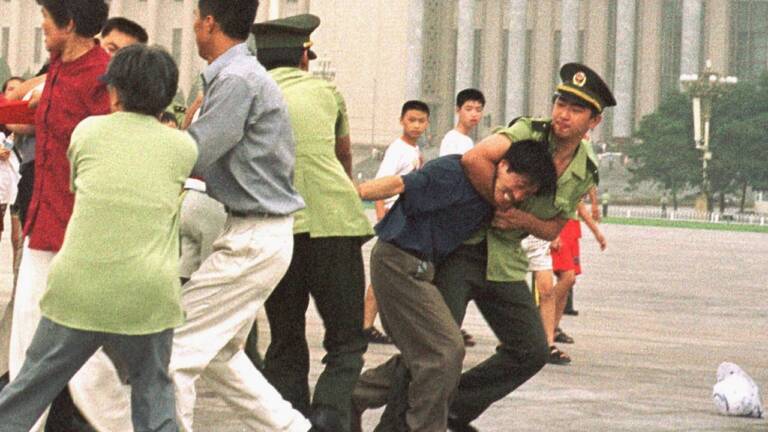

The main focus is China, where the number of new cases has plummeted in

recent days. Chinese officials, embarrassed by the devastating effects of

hiding the epidemic for so long, are eager to have the health agency remove

travel advisories and to show the world that, in the end, they can contain

the disease.

The health agency says it needs to learn much more about how China is

reporting SARS cases for it to gain full confidence that the epidemic there

is truly waning. “It’s not the quantity of cases, it’s the quality of the

data,” Heymann said. “We depend on what is reported.”

One possible explanation for the sudden drop in the number of SARS cases

would be if China had classified a case as suspect that other countries

considered probable. Only probable cases are reported to the WHO.

Because SARS is transmitted mainly from person to person, the health agency

is deeply concerned that epidemiologists have not determined the source of

the virus in about half of new SARS cases in China. The health agency also

wants to know what quarantine measures China is using and whether they are

working better than elsewhere.

Yet another area of uncertainty, the health agency said, concerns an

unconfirmed news report that scientists in China have found the SARS virus

in a wider variety of animals than previously reported. The new species

include snakes, wild pigs, bats and monkeys, though not household pets,

according to statements made at an Asian scientific meeting in Beijing.

In May, scientists reported finding the virus in masked palm civets and

raccoon dogs, and evidence of infection among badgers in a wildlife market

in Shenzen, in southern China. The WHO has received information about the

Shenzen findings but little about the newer findings despite telephone calls

to Chinese scientists, said a frustrated Dr. Klaus Stoehr, who directs the

scientific investigation of SARS for the UN health agency.

“I’m a bit astounded” by the report, Stoehr said by telephone from Geneva.

“If this virus is present in so many species, it would be a big surprise

biologically” because most viruses do not infect such a broad range of

animals.

Yet, if verified, the findings “would change the ball game,” Stoehr said,

“making control of SARS much more difficult, without doubt, because there

would be so many sources” of potential spread.

China is conducting research aimed at finding the source of the SARS virus.

Researchers from three centers in China have collected more than 3,900

samples from more than 60 animal species in markets, restaurants and hotels,

Stoehr said.

But, he said, the WHO has not yet received the information it needs to

evaluate findings stemming from this research, like details about the

methods the scientists used, what form of virus was found and how often

evidence of the virus was detected in different species.

The information is important because the presence of the SARS virus in a

number of species could lead to new cases, possibly on a seasonal basis,

depending on the animal’s habitat and behavior, even if the transmission

chain is stopped now.

SOURCE: The New York Times