(Commentary. William Pesek Jr. is a columnist for Bloomberg

News. The opinions expressed are his own.)

Hong Kong(Bloomberg) — Five years ago, China was

ecstatic to regain control of its long lost Golden Goose. Many

regarded Hong Kong as such at the time because of its unusual

dynamism and affluence.

These days, Beijing is wondering what to do with the place.

Hong Kong is no longer laying golden eggs, and if it’s providing

any goose eggs at all, it’s in the area of gross domestic product.

The city has fallen on hard times punctuated by worsening

deflation, rising unemployment and growing pessimism.

Things may only get worse if the government gets its way.

It’s angling to clamp down on the civil liberties of Hong Kong’s 7

million people with a new anti-subversion law. If passed in

anything resembling its current form, it would have a chilling

effect on an economy long cherished as one of the world’s freest.

Talk about putting a noose around the Golden Goose.

Journalists, investment banks and average citizens fear the law

will hamper free speech and stifle the exchange of new ideas.

Amnesty International and other groups warn the step could damage

Hong Kong’s standing as a global banking and business center.

The British Chamber of Commerce warned that the new law would

cause an exodus of foreign investors. The American Chamber of

Commerce worries government officials aren’t being “as sensitive

as they should to issues that will come back and haunt them.”

Bankers fear the new law may restrict access to and discussion of

information and data investors need to make decisions.

Basic Law

“We in Hong Kong have the obligation to uphold the

principles that have allowed us to grow and prosper and become the

dynamic community that we are today,” says David Li, a local

legislator representing the city’s banks.

Under Article 23 of the Basic law, Hong Kong’s constitution,

the government is obliged to enact laws prohibiting treason,

sedition and subversion. What’s troubling, however, is the vague

language being used to write them. While it would punish those who

divulge “state secrets” or take actions that “endanger the

stability” of China’s government, the law is anything but

specific as to what that means.

In the wrong hands, such ambiguous language could be used to

punish seemingly minor offences. If a Hong Kong-based economist

published a report suggesting China’s gross domestic product is

overstated, would that be an act against the state? Could an

analyst be punished for publishing negative economic forecasts?

What about a journalist who gets leaked information about a

politician or a company doing dodgy things?

Cautionary Tale

Here, the tale of Ho Cheuk-yuet may be a cautionary one. In

September, the analyst at state-owned BOC International (Holdings)

Ltd. recommended that Hong Kong scrap its 19-year-old peg to the

U.S. dollar. It was a perfectly reasonable point and one myriad

others around the globe also have made.

Ho “resigned” last month, a day before Chinese Premier Zhu

u 59/64Rongji visited Hong Kong and said he hoped the bank “will not

make the same mistake again.” Quite a coincidence, eh? If such

things happen even before Hong Kong passes it’s anti-subversion

law, imagine how things will be next year when it does.

Freedom of expression has always been the litmus test of

China’s commitments to uphold economic and other liberties here.

Beijing also has benefited from Hong Kong’s status as a Chinese

city with a Western-style legal system and free press. That

arrangement helped it lure the regional head offices of marquee-

caliber investment banks such as UBS AG and Goldman Sachs Group

Inc. Why meddle with things?

Economic Dynamism

There’s little reason to think China can’t suppress debate

here too. Trouble is, China has far more to lose than gain from

pushing Hong Kong authorities to gag investment banks, academics

and journalists. Hong Kong already has lost much of the economic

dynamism that once propelled it to greatness. Muzzling free

expression can only accelerate the process.

Even the undemocratic way Article 23 is being handled is

troubling. It’s being written behind closed doors, with no room

for public discussion about its contents or their implications.

The government has released a broad outline of how the law will

look, but refuses to offer more details on its wording.

China is missing a key economic ingredient: Self-confidence.

When you think about the world’s most vibrant, efficient and

entrepreneurial economies, what they have in common is a sense of

certainty. Not so much in the success of their policies, but in

the belief that right or wrong, their nation and economy will

Bsurvive intact. Beijing’s insecurity sends exactly the opposite

message — that things are too shaky to allow free speech and

transparency.

Sign of Weakness

Far from being signs of strength, limiting debate and the

flow of information is a sign of weakness. Beijing, of course,

disagrees with this assertion.

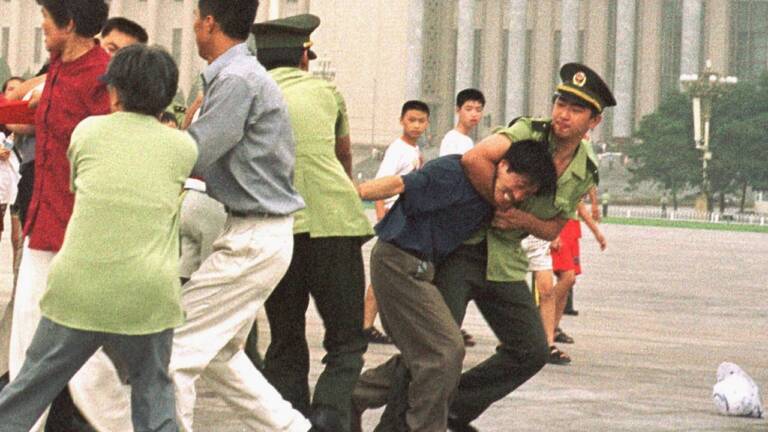

But if China is a mighty, solid power, why is it still

quaking in its boots over religious groups like Falun Gong or much

smaller ones? Why do leaders still lose sleep over academics

questioning their decisions? Who cares what talking heads say? Or

what Web surfers find with Google Inc.’s Internet search engine?

China recently blocked it to shield users from viewing “harmful”

information.

China is one of the world’s oldest civilizations. It’s the

most populous nation and in 2002 once again boasted the fastest

growth rate anywhere. You’d also be hard-pressed to find many

observers who think China isn’t a rising economic power. And yet

so much time and energy goes into controlling what’s said about

China — and done toward it.

That tendency is increasingly spreading to Hong Kong and the

economy could suffer for it.

Posting date: 20/Dec/2002

Original article date: 17/Dec/2002

Category: Open Forum