Two truths about Falun Gong: it is not a religion, and the Chinese government

seems to want it crushed at any cost.

A highly spiritual practice that combines

philosophy, meditative aspects and specified body movements, drawing on Buddhism

and Taoism to explain its teachings, Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, has

snowballed over the past few years into a veritable synonym for Chinese state

persecution.

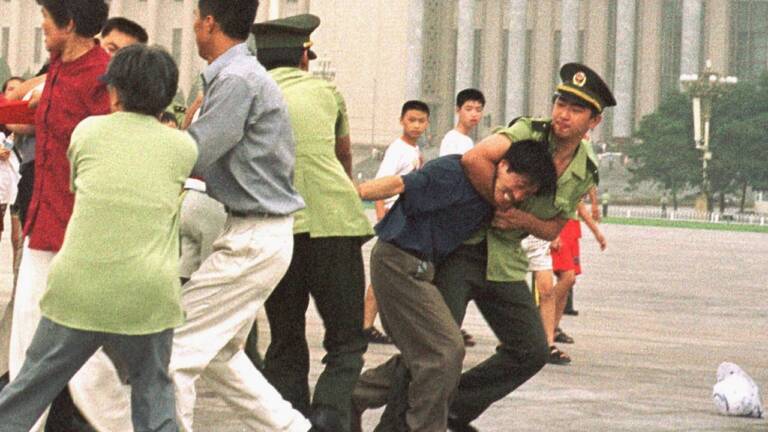

Banned by Beijing as "an xx," "the common

enemy of mankind" and "responsible for many cruel killings and crimes,"

among other epithets, Falun Gong’s supporters say that in China, practitioners

have become targets of systematic incarceration, torture and murder.

Supporters

also warn that Canada is not exempt from a global Chinese campaign of hate propaganda,

spying on and harassing Falun Gong followers.

And they’re using the current

visit to Canada of China’s president, Hu Jintao, to bring the issue to the fore.

Hu was scheduled to visit Ottawa and Toronto between Thursday and tomorrow,

with a side trip to Niagara Falls. His delegation will travel to Vancouver Sept.

16 and 17.

In a letter to Prime Minister Paul Martin urging him to call

on Hu to end the persecution, the Ottawa-based Falun Dafa Association of Canada

claims that more than 2,780 deaths of practitioners while in police or government

custody have been verified, 757 of those between May and July of this year.

The

group accuses Beijing of employing more than 100 methods of torture, including

rape, force-feeding and electric shock.

International human rights groups

say the number of practitioners who remain in illegal custody is in the thousands.

On Wednesday, supporters rallied at Queen’s Park with banners and live

displays of torture. They called for the release of 18 jailed family members of

Canadians, most of whom reside in Toronto, and for officials here to bar the entry

into Canada of Bo Xilai, alleged to be responsible for overseeing the torture

and killing of hundreds of Falun Gong practitioners in China’s Liao Ning province.

Falun Gong advocates are still steamed that the federal government last

month deported a practitioner back to China. They fear that 54-year-old Hu Xiaoping

is now in grave danger.

Ottawa has said it would raise the overall issue

of human rights in China during the visit of the president, who took office in

2002 and has continued his predecessors’ suppression of Falun Gong. The bloody

crackdown began on April 25, 1999, when 10,000 adherents gathered outside the

residential compound of Chinese Communist Party leaders in a daring but illegal

protest against sporadic persecution.

Falun Gong was then banned as "a

threat to social and political stability."

The U.S. Congress has passed

several resolutions criticizing Beijing on Falun Gong. In October 2002, the House

of Commons unanimously passed a motion requesting the release of 13 Falun Gong

practitioners, among them Lizhi He.

An award-winning civil engineer in

China and Falun Gong practitioner since 1995, He was arrested in July 2000 in

Beijing after he mailed several letters to friends in which he extolled the virtues

of the practice and countered the government’s hate campaign.

Following

a show trial in December, 2000, He was sentenced to three-and-a-half years for

"inciting social disturbance," despite the fact he had received a visa

to become a permanent resident in Canada.

For the first seven months of

his detention, He was held in a detention centre in Beijing, where his wife was

not allowed to visit him. He was kept in a 20-square-metre cell with 30 other

prisoners.

"I was forced to sit motionless and I was monitored by

four inmates," He said in an interview. "If I moved even slightly, I

was beaten. Every day, my underwear clung to my bloody skin."

He developed

a fever and chest pains, but was transferred to a prison where, barely able to

stand, he was forced to perform military drills in the freezing wind and rain.

He began to cough and urinate blood, and was finally taken to a hospital. "Even

there, I was pressed for information about my fellow practitioners," he recalls.

After 50 days, He was returned to prison, where he endured shocks with

batons and was forced to write statements of self-criticism every day.

Amnesty

International declared him a Prisoner of Conscience.

"I suffered tremendously,"

He says gently.

Now a 41-year-old engineer living in Scarborough, He harbours

no ill will toward his torturers. "It’s not a personal hatred, but they will

have to pay for what they did. I can forgive them."

Fellow practitioners

will recognize in He’s attitude at least one of the three basic moral principles

on which Falun Gong operates: Zhen, Shan and Ren, or truthfulness, benevolence

(or compassion), and forbearance (or

tolerance) – historically Buddhist, Taoist

and Confucian virtues.

Practitioners are encouraged to conduct themselves

with all three in all situations to develop their xinxing (moral character).

The

goal is to cultivate one’s mind, body and spirit in order to reach higher levels

of consciousness, aided by a set of five exercises.

About 30 practitioners

representing a wide range of ages and backgrounds gathered on a clear Sunday morning

in August in front of Mississauga’s city hall, one of about a dozen "practice

sites" in the GTA, for two hours of consciousness raising.

While a

tape plays soft Chinese music and a voice gently calling instructions, practitioners

begin in a sitting position, either cross-legged, half-lotus or full lotus. Eyes

are closed and hand positions change roughly every five minutes. This lasts an

hour, and requires obvious discipline (in joining the group, this reporter found

he had to shift sitting positions several times).

Then comes another hour

of four standing exercises, also involving various hand positions. Breathing is

normal at all times.

The routine is often confused with Tai Chi, but Falun

Gong’s movements are crisper and said to be easier to learn.

"The

most important aspect of the teaching is to always know that you’re here doing

the exercises, and to help strengthen your main consciousness,"

says

Joel Chipkar, a 37-year-old Toronto real estate broker and spokesperson for the

Falun Dafa Association of Canada. The effort aims to "realign and rebalance

the body’s energy. There’s no trance, no visualization, no meditation. It’s a

very bare awareness."

And, he points out, it’s all free of charge.

There’s no official "membership."

The routine ends with readings

from Zhuan Falun, the movement’s text, which teaches that a Falun, or "A

Wheel of Law," resides in the lower abdomen of practitioners. Said to be

a miniature of the universe, it turns continuously. When the Falun turns clockwise,

it absorbs energy from the universe into the body; when it turns counter-clockwise,

it rids the body of negative influences.

The basic teachings seem to combine

the compassion and mindfulness of Buddhism with the self-improvement techniques

of Dale Carnegie: Don’t fight with others. Reduce your attachments. Treat others

with kindness. Cultivate and live a peaceful life.

Even so, Chipkar made

headlines last year when he successfully sued China’s deputy consul general in

Toronto for libel. In a Star letter to the editor, Pan Xinchun had called Chipkar

a member of a "sinister cult" designed to "instigate hatred."

The court agreed Chipkar had been defamed and awarded him $11,000 in damages,

of which he’s seen not a penny. Pan skipped town, supposedly back to China, and

attempts to seize his bank account failed.

Raised, as he puts it, in a

hot-blooded, short-tempered, southern Italian family, Chipkar says Falun Gong

"taught me to treat others with kindness and compassion and always look inside

to see what you can do better. It changed my life."

Founded in 1992

by Li Hongzhi, a 54-year-old former grain clerk from northeastern China who now

lives in seclusion in Brooklyn, Falun Gong (roughly, "Practice of the Wheel

of Law") spread quickly. Along with other related movements, such as Ch’i

Gong, it was viewed favourably by Beijing, says David Ownby, a China expert at

the University of Montreal who’s finishing a book on Falun Gong.

Chinese

spiritual and cultural traditions, Ownby notes, have historically stressed physical

health and longevity. One outgrowth was Ch’i Gong, a cultivation method that combines

stretching and slow movements.

"Ch’i Gong passed itself off as magic

and physiotherapy," he says. "The (Chinese Communist) party loved it

because (its leaders) are all old, and it seemed to help. Falun Gong followed

right along."

But when the April 1999 demonstration took place, the

Politburo panicked.

"The size and unexpectedness of it made them think

this is not a national treasure anymore. Ten thousand people right outside – that’s

spooky.

Anything that big is really scary to China’s leaders. It brought back

memories of 1989 (the Tiananmen Square massacre), and they were ready to pounce."

Numbers are nearly impossible to assess, Ownby adds. While Li Hongzhi claims

100 million followers worldwide, 80 million of whom are in China (making it larger

than the 60 million members of the Communist Party), Beijing says the group has

just two million practitioners. Both sides have been accused of misestimating

numbers for their own purposes.

And in a nation where only five religions

– Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism and Protestantism – are recognized and

strictly controlled by the (officially atheistic) state, senior cadres may have

also feared a spreading spiritual movement that was outside their purview, Ownby

says.

Falun Gong has also acquired a bit of a kooky label due to founder

Li Hongzhi’s theory that corrupt aliens are fixing to replace humans.

Extra-terrestrials

are also responsible for our too-rapid advance in technology.

Chipkar downplays

the supernatural element.

"I believe the universe is boundless. It’s

very egotistical for human beings to think that we’re the only ones in the universe."

Is the alien influence possible? "Yes," he replies. "Have I seen

it? No. Has anyone else seen it?

Maybe. But for me to dwell on that would

be not to follow the principles of Falun Gong. It’s just information. You take

it or leave it."

Beyond Falun Gong’s beliefs, China’s leadership,

still deeply suspicious and paranoid, clearly views the movement as a threat.

As Hu’s predecessor, Jiang Zemin, was reported to have told a 2001 meeting of

the Chinese leadership, "If we can’t exterminate the cult soon, this will

be seen as a major weakness of the Communist Party. The authority and prestige

of the party is at stake."

No one from China’s embassy in Ottawa returned

calls for this story.

Posting date: 17/Sep/2005

Original article date:

10/Sep/2005

Category: Media Report