She had her legs and wrists bound, her mouth taped over and her body and soul

battered, but, as Tang Yiwen tells Hamish McDonald, she never gave up her faith

in the Falun Gong.

Tang Yiwen seems to materialise from nowhere when she approaches

at the agreed rendezvous outside a Beijing restaurant. She cuts a nun-like figure

in a girlish dress, white ankle socks and black shoes.

Tang’s conversion

to Falun Gong followed a familiar pattern. Tang, or Amelia as she also calls herself,

had been an especially bright student at her high school in Maoming, a town in

Guangdong province not far from the provincial capital Guangzhou. She won a place

at a top foreign languages university in Beijing, emerging at the top of her graduating

year in Japanese as well as teaching herself excellent English. Back in Guangzhou,

she soon prospered as an interpreter for visiting Japanese delegations and, with

a friend, invested in a new restaurant.

Tang, 37, says that as she headed

towards 30 her life seemed empty. She suffered aches and pains which expensive

visits to doctors couldn’t cure.

She had been estranged from her parents for

years: her father, a Korean War veteran of the Chinese military, followed stiff

patriarchal ways. She couldn’t commit to marriage with her boyfriend of long standing,

another Japanese translator.

"Most devastatingly it was a spiritual

problem," she says. "Growing up in China, our minds were just stuffed

with empty communist ideas. We didn’t have any chance, like the Bible said, to

get any education, any perceptions, any ideas about love, mercy, forgiving, and

what was the meaning of life and humanity. Only very false, empty, shallow Chinese

Government communist ideas."

Her sister, Lisa, who had lived in Sydney

since 1989, meanwhile had taken up Falun Gong after hearing its founder, Li Hongzhi,

speak in Sydney in 1996.

Visiting Maoming, Lisa radiated a new serenity. Tang

decided to try out the Falun Gong exercise routines and soon her aches faded,

while the movement’s moral code made her feel a new, "less selfish"

person. She dropped her interpreting job, started teaching at a commercial college

for much less money and married her boyfriend. "It changed me slowly,"

Tang says. "I am becoming the person I have always wanted to be. I have found

the person."

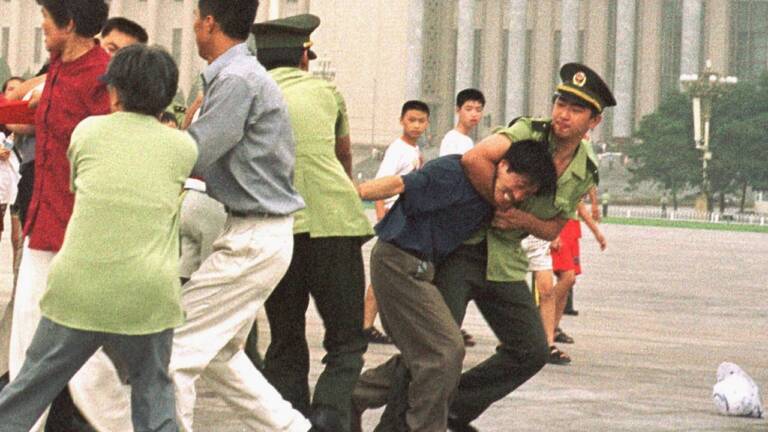

Then, after Falun Gong was officially banned in 1999,

she was pressured into quitting her teaching job. The next year she travelled

to Beijing for Falun Gong’s special date of May 13, which marks Li Hongzhi’s claimed

birthday, and went out with other practitioners into Tiananmen Square to protest.

She was arrested immediately and handed over to Guangdong police. She was released

after seven days of a hunger strike.

The police came again, and on August

23, 2000, sent her for two years of reform-through-labour. They took her across

the river to Chatou, where a few hundred Falun Gong women shared crowded barracks

with female drug users, prostitutes and petty criminals. The days were spent in

sweaty workshops, on 10-hour shifts processing goods brought in by Guangzhou manufacturers:

artificial flowers, fluffy toys and tablewear.

Throughout her two-year

sentence, extended by a year for recalcitrance, Tang says she was under daily

pressure to sign letters renouncing Falun Gong.

Periodically she and other

practitioners were taken to detention rooms. The criminal prisoners would be drafted

to read aloud for hours from anti-Falun Gong government tracts. Loudspeakers and

monitors would repeat the same propaganda videos at high volume, accusing Falun

Gong of murder and mass suicide.

"At the end of the day, you have

to write your so-called homework before you’re allowed to go to sleep," she

says. "They give you a topic: what do you think of your position here as

a prisoner? You are supposed to be a teacher, teaching outside, what do you think?

What do you think of your master running away to America, having a good time,

and you practitioners so foolishly suffer here? Don’t you feel cheated by him?

Don’t you think you’re doing terrible things against Chinese law."

For

the first year, Tang says, she used the homework to try to explain her beliefs.

"We thought we could communicate, get the police to understand us,"

she says. "But we found out they weren’t really reading it, they were

just trying to find out something they could use as a weapon to attack you back.

In the last year I refused to write at all and told them it was no use …

It prolonged my sentence an extra year."

In October 2002 Tang

was taken to a room. Her legs and wrists were bound, and her mouth taped over.

Teams of interrogators forced her to stand up to 19 hours a time as they shouted

insults, slapped and kicked her.

The two women leading the interrogation

were Falun Gong specialists sent down from Beijing, named by Tang as Zhang Lijun

and Yue Huiling.

"When they got tired they would chat to each other

cheerfully, laughing loudly," she says. After long stretches of this punishment,

she would be released, forced to stand up, then be tied up again even more painfully.

After three days Tang was sent back to her dormitory, barely able to walk.

Cries came from other prisoners receiving the same treatment. The camp’s staff

were said to be trying to meet a quota of Falun Gong conversions linked to the

Communist Party congress being held around that time. Two months later Tang went

through the same experience, until a camp doctor warned interrogators they would

have to let up. Her right leg has remained stiff and painful ever since.

Early

last year the interrogators seemed to give up. In February her father had talked

his way into seeing her. Shocked at her injuries and appearance, the old soldier

began firing angry letters and queries to Guangdong officials. Released prisoners

had also begun spreading the names of their oppressors in the camps and these

were starting to appear on websites. Even the more strict jailers may have begun

to realise they were prime scapegoats in any clean-up campaign that Beijing might

launch to appease foreign critics.

In May last year Tang was shifted to

a labour camp in outlying Shanshui, where the conversion effort continued, but

with less violence. Her husband came to visit, telling her he wanted a divorce.

He was tired and frightened by the constant police harassment. "Reality is

more important than the ideal," he told her.

On her release from Shanshui

in August last year he came to pick her up, then, with his mother ringing on his

mobile urging him not to stay, he left her at a hotel.

Newly reconciled

with her father, who had hugged her in Chatou for the first time she could remember,

Tang went back to Maoming, but was under constant watch by the local 6-10 office,

named for the date in 1999 when the then Chinese leader, Jiang Zemin, is thought

to have decided on the crackdown.

Potential employers and friends were warned

off.

Then on February 23 she was picked up by a group of six officials

as she walked on a Guangzhou street and was taken to the Guangzhou City Law School,

a "brainwashing centre" for those who still refuse to renounce their

beliefs after years of punishment at the labour camps.

"Many fellow

practitioners had told me it was more brutal than the labour camp," she says.

"I knew what would happen." She announced the start of a hunger strike,

refusing to talk, eat or drink. As she lay weakening, alone in her cell, doctors

were brought in to feed her through tubes.

From distant parts of the building

she could hear sounds of distress. "Often I could hear some thumping sound,

some grunts, struggling noises like someone being beaten," she says. "Then

I could hear guards running towards the sounds."

Officials tried to

persuade her to give in. "’You are going to die here,’

they told me.

‘You will have lots of chronic illnesses; you will never have children,"’

Tang says. "They kept giving me names of practitioners who had gone on hunger

strike and what diseases they developed."

A senior official in the

Guangzhou Political and Legal Committee, the party organ supervising the 6-10

offices, came to see her. She asked him why she was there. He replied: "It

was necessary for you to receive legal education.

Because you are still persistent,

you still believe in Falun Gong, we can put you in here. This is what our country’s

law requires."

Tang also asked him how they had found her in a city

street. "No matter where you hide, we can finally track you down, unless

you go abroad," he said. "But you know, people like you cannot go abroad."

After 20 days Tang was taken to a Guangzhou hospital and her parents summoned.

The guards refused to give her up until her mother signed a paper exonerating

the law school from any responsibility.

In June Tang smuggled out a handwritten,

seven-page letter to John Howard’s office, setting out her difficult position

and asking to be allowed into Australia where she had her sister and the promise

of employment. A reply arrived, saying that the Prime Minister had referred her

case to the Foreign Minister, Alexander Downer, and the Immigration Minister,

Amanda Vanstone.

In any case, Tang did not wait for the reaction from her

watchers in Maoming’s 6-10 office. On August 9 she slipped out of her parents’

flat late at night to avoid being reported by the building’s janitors, went into

Guangzhou to finalise her divorce, then began a series of train trips that eventually

took her to Beijing.

Tang now spends her days meditating, reading her well-thumbed

copy of Li’s writings or listening religiously to his voice on tape. She survives

on tiny amounts of fruit, rice and bread, drinking only water.

She still

wants to move to Australia. "There is nothing for me here now,"

she

says. Her life has dwindled to her self-cultivation and devotion to Falun Gong.

She insists her full name and details be used in this report, whether it helps

get her out of China or brings more punishment from the Chinese police.

She

believes that communist rule is coming to an end, an expectation she says is widespread

in China. "I respect Master Li and I fully trust him, even though I have

never met him in person and he is so distant away in body from China," she

insists. "It is not out of thoughtless impulsiveness or out of ridiculous

worship, like many Chinese people did previously towards Mao Zedong."

Australia

is no longer doing anything for Tang, and she was not mentioned during Thursday’s

meeting of Australian and Chinese officials in Canberra for the annual bilateral

human rights talks. The Government had raised her case "several times"

during her imprisonment, according to an Australian embassy spokesman. "Now

that Ms Tang has been released and in the absence of evidence that she is being

subject to ongoing human rights abuse, the Australian Government has no grounds

to pursue her case further with the Chinese Government."

After

five years people such as Tang Yiwen are much fewer than they were.

Falun

Gong members make up only 3 or 4 per cent of those inside labour camps, says Frenchman

Nicholas Becquelin, who directs the Hong Kong office of Human Rights Watch, founded

by exiles of the 1980s democracy movement.

But the Chinese police still

mount a pervasive vigil against Falun Gong protests, which have included the hijacking

of signals on state television channels to broadcast the group’s own messages.

Overseas, Falun Gong members continue to sit in lotus position outside

Chinese embassies and consulates, and picket Chinese delegations, while highly

educated spokesmen lobby governments and the media to get Falun Gong persecution

onto the international human rights agenda.

Counter-efforts by Chinese

diplomatic personnel include the monitoring of Falun Gong members, contact with

family members to warn them about the alleged dangers of membership and heavy

pressure on local authorities to keep Falun Gong out of officially sponsored events.

Meanwhile Becquelin complains about certain exaggerations by Falun Gong,

and about the movement’s lack of interest in others suffering similar repression,

though he acknowledges it has been the target of China’s "largest persecution

campaign or systematic human rights abuse since 1989".

To most outsiders,

the prevailing image of Falun Gong is of mostly middle-aged or older practitioners

doing harmless exercises in parks, following the wacky writings of yet another

charismatic guru.

Where that leader, Li Hongzhi, takes his followers from

here remains to be seen.

Benjamin Penny, a religious historian at the Australian

National University, says Li’s official story follows a conventional pattern in

Chinese religious biography, taking the subject from a mundane existence into

another form: ascending bodily into heaven or entering nirvana.

In Li’s

case, the last chapter is not yet written. Available to most of his followers

only in cyberspace, Li now refuses all approaches from journalists and others

outside his movement. He did not respond to interview requests for this report.

As far as Beijing is concerned, all the evidence points to the fact that

suppression is only increasing the stubborn belief of Falun Gong adherents like

Tang.

"But it is virtually impossible for the Chinese leadership to

stop now, given the amount of face which has been invested," says Barend

ter Haar, an authority on Falun Gong at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2004/10/15/1097784049016.html?oneclick=true

Posting

date: 16/Oct/2004

Original article date: 16/Oct/2004

Category: Media Report