By Hamish McDonald, Herald Correspondent in Beijing October 16, 2004

Tang Yiwen … she claims the state tried to bully her into denouncing

Falun Gong.

A small nameplate beside the high, burnished metal gates announces

the building inside as "Guangzhou City Law School". But this grimy industrial

area on the outskirts of China’s great southern commercial metropolis is an unlikely

place for an academic institution.

No students are visible. The only signs

of life are the black official cars and police vans that come and go through the

forbidding gates. Nearby, across the Pearl River, is a grim set of barracks, called

Chatou, behind high walls and watchtowers.

According to one woman who has

been inside, the school is a front for a state gulag, where police re-educate

followers of Falun Dafa, a quasi-religious movement based on meditation and taichi-like

exercises that was banned by the Government five years ago as a "dangerous

cult".

"It is a brainwashing centre – one of many in China, almost

one in every district," says Tang Yiwen, a slight and soft-spoken 37-year-old

interpreter who was grabbed off the street by police in February and taken to

the Guangzhou institution. "It is said to be one of the most brutal."

She said the inmates are mostly Falun Gong followers who, like her, have

refused to renounce their beliefs even after serving three to four years in brutal

labour camps like the one across the river.

She said the school put inmates

through an intensive program of mental and physical torture that included beatings,

prolonged interrogations, sleep deprivation and continuous exposure to video and

audio propaganda.

The "brainwashing", she said, was a more intensive

form of "re-education" applied to Falun Gong followers in between stints

at places like Chatou and Shanshui, the labour camp in Guangdong province where

Tang spent three years until August last year. She said her visit to the Guangzhou

City Law School has left her partially crippled in one leg.

The methods

she and others describe sound eerily like the "struggle" sessions applied

by Mao Zedong’s Red Guards to extract confessions of "rightist deviation"

during the decade-long Cultural Revolution Mao set off in 1966.

"I

used to hear from my father and old people how people, one a famous writer, had

committed suicide in the camps," Tang said, referring to that era. "I

couldn’t understand. Why couldn’t they just hold out? After brainwashing in labour

camp I understood why – it was really too brutal for human beings to stand. It

was just like hell."

On the face of it, the struggle between state

and Falun Gong is a hopelessly uneven one, like the breaking of a butterfly on

a wheel.

On one side is the 1.7-million strong Ministry of Public Security,

which is directed by Liu Jing, 60, a party central committee member with connections

to the family of the late supreme leader Deng Xiaoping. The police can hold people

without trial or access to lawyers for up to four years.

There is also

the full weight of the state propaganda department, which directs a hostile media

campaign against Falun Gong, claiming the movement encourages suicide and neglect

in adherents and takes their savings.

There is no legal redress for abuses:

after the official ban in July 1999, the Chinese Supreme Court passed down a directive

forbidding lower courts or lawyers to accept cases brought by followers.

On

the Falun Gong side are people like Tang. She is crippled, unable to get a job

in the teaching profession she loves and at risk of being jailed and tortured

at any time. She said her husband was forced to divorce her, and she cannot get

a passport to leave China.

Since receiving a pro-forma letter early in

August from the office of the Australian Prime Minister acknowledging a smuggled-out

account of her ordeals and her request for asylum in Australia, Tang has been

constantly on the move, staying in a succession of temporary accommodations around

China, fearing re-arrest by embarrassed and angry police.

Yet the butterfly

is not broken.

It is not too hard to find people who – even after years

in labour camps – still swear by Falun Gong. In her three-week battle of wills

inside Guangzhou City Law School, which involved a hunger strike that brought

her close to death, Tang came off the moral victor: she was released without signing

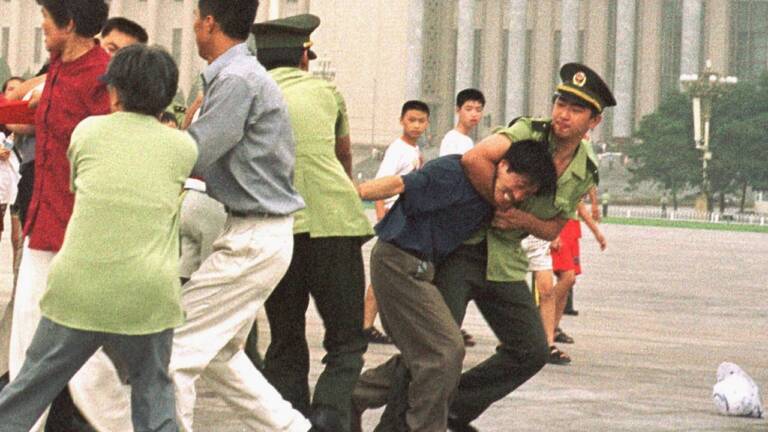

any of the letters of renun-ciation waved in front of her. WHEN more than 10,000

Falun Gong followers arrived without warning early on April 25, 1999, outside

Zhongnanhai, the walled precinct next to the Forbidden City where China’s ruling

elite live and meet, and sat down in silent protest, it was an enormous shock

to China’s then party chief and president, Jiang Zemin.

Falun Gong had

grown exponentially since it was formally registered in 1992 by Li Hongzhi, a

former army trumpet-player and minor clerical worker in China’s bleak north-east,

formerly known as Manchuria, where millions were suddenly losing their jobs and

social welfare benefits with closure of obsolete factories owned by state enterprises.

Partly out of legal necessity – Beijing does not allow new religions outside

the streams of Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism and Protestantism – Li positioned

Falun Gong among many groups reviving the ancient form of bodily and mental cultivation

known as "qigong" whereby the life forces (qi) can be channelled into

beneficial harmony by meditation, diet and slow-motion exercises (gong).

But

in contrast to more secular, often pseudo-scientific groups, Li claimed to have

rediscovered the basic law (fa) of the universe, as well as gaining supernatural

powers through the teaching of a score of qigong masters since the age of four.

"Master Li" could see through objects, or transmute himself through

closed doors. He was a "Living Buddha".

For ordinary practitioners,

Falun Gong’s routine of daily exercise provided an immediate sense of well-being,

as well as a fall in the medical bills that had become so expensive under China’s

market reforms. Many reported that chronic ailments, even serious illnesses, simply

faded away. The movement’s simple moral code – truth, benevolence and forbearance

– also gave a psychological lift to anxious people living in crowded tenements.

Li’s two widely-circulated books, which practitioners were told to read and

absorb daily, gave them the goal of self-purification.

By the late 1990s

some Chinese media claimed it had 100 million adherents.

The Government later

amended that figure to 3 million, but the reality was probably in the tens of

millions, concentrated in northern China.

Master Li, who by 1998 had moved

to the United States, had shown no interest in exerting any political power. Falun

Gong’s methods were entirely peaceful, and the organisation showed no concern

with social ills – beyond telling followers to rise above them through self-cultivation

and superior morality.

But the evidence of the movement’s ability to organise

was alarming to the Communist Party. Falun Gong’s membership included many state

employees, party members, and armed forces personnel. When the state media made

a slighting reference to Li, hundreds of followers had protested outside a state

TV station in Tianjin, and then, unsatisfied, marched on Zhongnanhai.

It was

the biggest challenge to the state since the Tiananmen Square massacre a decade

earlier.

Jiang unleashed a suppression campaign, with a ferocity that intensified

as Falun Gong followers streamed into Beijing for continuing protests. The skill

with which Falun Gong has fought the propaganda war since the ban, noted the French

scholar Benoit Vermander, reinforced the impression the communists had met their

toughest adversary since taking power – "an adversary that knows all there

is to know about the party".

http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2004/10/15/1097784050386.html?oneclick=true

Posting date: 16/Oct/2004

Original article date: 16/Oct/2004

Category:

Media Report