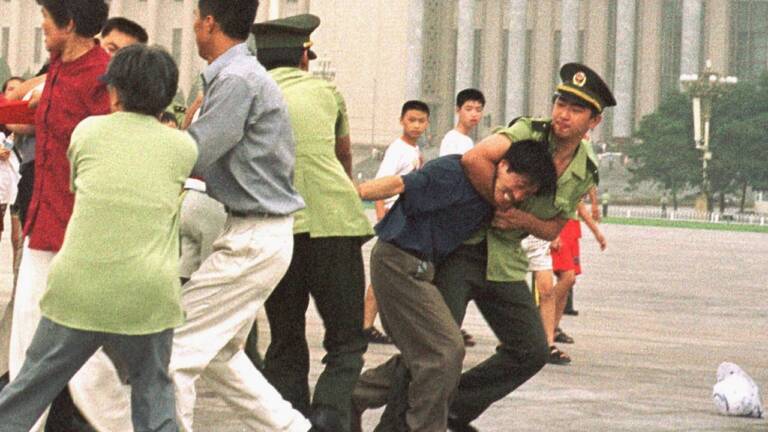

A Western Falun Dafa Practitioner

Camellia sinensis, these two words, the botanical name, means nothing to most

people, unless they are familiar with camellia flowers or are aware that “sinensis”

means “Chinese.” Tell anyone, however, that Camellia sinensis is the

plant that produces tea, “thea sinensis,” and a knowing smile will

his face will certainly evoke pleasant memories. Just what is it that has made

the drinking of tea so enduring for thousands of years?

Tea lore abounds. Origins of tea-brewing stories vary, depending on who does

the telling. People have sung the praise of tea for millennia. Emperor Chien

Lung (1710-1799) who lived during the Manchu Dynasty expressed his fondness

this way:

“You can taste and feel but not describe the exquisite state of repose

produced by tea, that precious drink which drives away the five causes of sorrow.”

Although he did not explain what these five causes are, I believe him. Whenever

I am about to read from the most precious book in the world, Zhuan Falun, I

first take a cup of freshly brewed tea in hand and sip slowly, calming my senses

and focusing my mind.

Others throughout history, the lowly and highborn, have documented and are

today again lauding the benefits of this ancient beverage. China grows the bulk

of all teas consumed in the world.

Camellia sinensis, that evergreen shrub which is the source of much pleasure

and enjoyment, can grow as tall as 30 feet. When the shrub is cultivated for

tea leaves and not for lumber as it is in parts of Malaysia, the shrub is pruned

into bush form, not more than five feet tall, allowing the picker to reach every

branch, and permitting the plant to expends its energy to produce leaves instead

of height. Regular pruning every three years keep the shrubs to the desired

height. All teas marketed come from this plant, but the types of tea, as varied

as people’s personalities, depend on several other factors, as is explained

further on. The quality of tea depends on stringent cultivation, just as people’s

character becomes nobler and more precious through proper cultivation.

Ancient Chinese stories relate that formerly only highly moral, virgin women

were chosen to harvest tea. It might be somewhat difficult to find enough young

women of such caliber nowadays, but I think the demeanor of the tea harvester

affects the quality of the gathered leaves.

Tea flourishes at elevations of up to 6,000 feet. Tea planters claim the lower

the elevation, the tougher the leaves of the bush. Connoisseurs insist that

teas grown at high altitudes have the most desirable flavors. Teas grown at

such heights are also costlier than those from lower fields because the terrain

makes them more labor-intensive.

The renowned Lu Yun, writer of the Ch’a Ching (The Tea Classic), asserted

in 780 A.D. that tea cultivation in China started by around 350 A.D. His estimate

is refuted, however, by an entry from a 350 A.D. Chinese dictionary that already

told of much earlier tea cultivation. Even before it was extensively cultivated

for use as an everyday drink, the Chinese had used tea as medicine, probably

not yet aware of phenols’ healing properties in tea, mentioned below.

Lin Yutang, a modern Chinese scholar, related a story that was discovered from

around 307 A.D., telling of many Chinese fleeing the invaders from the North.

They came across the Yangtze River to the Wu region, the area now called Shanghai,

where street stalls already sold tea to passers-by then. Other records hailing

from that period disclosed that tea has since then become an integral part of

daily Chinese life. But not all could afford the choicest teas or the best water

for its preparation. Some even made do with the sweepings from the tearoom floor

and brackish water.

From a tale entitled “Through a Moon Gate, by L.Z. Yuan we learn that

Chien Lung, the famous 18th Century Ching Dynasty Emperor, demanded not only

the best leaf but also the best grade of water for brewing. (Obtaining choice

water in China right now might be somewhat problematic, since 600 of the largest

cities in China are facing severe water shortages and the water quality is marginal).

While emperor Chien Lung toured his various realms, he rated the water quality

of their fountains according suitability for tea making and concluded that,

“the lightest water is best for tea-making.” His prize went to the

Jade Fountain outside Beijing, because “the water is the quality of melted

snow.”

Melted snow for tea water is again the topic in another story, that of an anonymous

writer from the 16th Century. In his novel Ching Ping Mei, Moon Lady, a character

in the story, goes into the snow-covered courtyard, sweeps a portion of snow

from the path and heats it in the tea kettle. To brew her tea, she uses a special

tea blend, “noble Phoenix and mild Lark’s tongue.” The brew enraptures

the guests, compelling one of them to pen this poem in gratitude:

‘In the jasper crock

Light puffs of crystalline vapor,

From the golden bowls

A wild, rare fragrance mounds.”

Those “golden” bowls may have been poetic license, or the term could

have referred to the glaze on the teacup, because no Chinese person would drink

tea from a metal cup, unless in dire circumstances. The earliest teacups were

pottery and later porcelain, around which a whole industry developed. The wealthy

could afford the finest porcelains from the choicest manufacture, adorned with

exquisite glazes and delicate designs. But other materials for teacups have

also been used, as I gleaned from a passage in the famous 18th Century novel

Dream of the Red Chamber, by Ts’ao Hsueh-Chi’n, where we are regaled

about a nun offering tea to guests:

“The matriarch asked her what it was and the nun answered that it was

rainwater saved from the year before… The nun then took Precious Virtue

and Black Jade into another room and made a special tea for them. She poured

the tea into two different cups… of the rare Sung period. Her own cup was

of white jade.”

Several dynasties were renowned for their porcelain, but none more so than

the Ming Dynasty. Teacups from that era were and are still highly prized. Some

survive as rare museum pieces, unequalled in workmanship, glazes and shape.

But back to the plant that fostered such a profusion of teacup manufacture,

many of them imitated to this day. Tea is indigenous to China, although 30 other

countries also grow tea. The most recognized are India, Japan, Taiwan, East

Africa, Russia and the former Ceylon, now called Sri Lanka. India is the largest

exporter of her tea crop; China exports tea to a lesser degree. My years of

tea consumption have found that the flavor of good Chinese/Taiwanese tea is

superior to teas grown elsewhere. What accounts for these variants?

The answer is the soil, proper moisture at the correct time and the methods

of wilting, harvesting, curing, drying, fermenting, blending and sorting the

leaves into the marketable product. China teas come primarily from five provinces,

Yunnan being the originator of the choicest teas because of the province’s

proximity to the Himalayas. I think that Yunnan tea is one of the world’s greatest

teas. Picked at high altitudes, it is free of astringency and full of rich flavor.

It is expensive, but a scant spoon full of tealeaves brews a nice pot. The four

other tea producing provinces, located in Eastern China, are Anhui, known for

her black Keemun tea, said to have an almost chocolaty aftertaste; Fujian and

Jiangxi (black teas, used primarily in tea blends) and the province of Zhejiang,

reputed for its gunpowder teas, a green variety. The leaves are rolled to look

like tiny gun pellets, hence the name.

All teas are harvested from the same plant, Camellia sinensis. The differences

arise from the types of the harvested tealeaves themselves and their processes

of withering, drying, oxidizing/fermenting, smoking, roasting and packing. The

choicest and most expensive teas are prepared from the first three leaves, including

the unripe tip at the top of the plant, harvested at exactly the right time.

Lesser qualities are from the next two leaves down on the branch. Three main

types of tea are available – non-fermented green tea, black tea, fermented

and Oolong (meaning Black Dragon), a semi-fermented tea, manufactured mainly

in Taiwan. “Chinese oolong tea is not one tea, but many different teas,”

as the Tea World website (http://get-orientaided.com) tells us. That site gives

a fairly accurate description how Chinese oolong teas are prepared for consumption,

the different examples of oolong, what accounts for the myriad of coloring in

the brewed tea, and also recounts charming tea lore. It also lists exhaustive

information regarding flavored Chinese teas.

Green tea is actually “fired,” meaning the leaves are placed in a

large iron basin for 20 -30 seconds and heated to 100 degrees Celsius. This

operation destroys the enzymes in the leaves that cause fermentation. This process

of “firing” renders the leaves a green color.

The flavor of green tea depends on the choice of the leaves used, the growing

region and also the length of storage. A Chinese friend told me that I could

“revive” tealeaves that have been stored too long by heating them

in the oven for a while before brewing. This, when brewed, would result in a

better cup of old tea.

Scientists have recently discovered that drinking green tea has immense health

benefits, because it contains many micronutrients, vital for keeping our bodies

healthy. An article in the Journal of Science of Food and Agriculture, Vol.

26, from 1975 entitled, “The Nutritional and Therapeutic Value of Tea”

has this to say about green tea:

“Green tea contains vitamin C in amounts comparable to lemon; vitamins

K and P (bioflavonoids) comparable to green vegetables… comparable to spinach

and beta-Carotene found in carrots. It strengthens the blood vessels, has anti-inflammatory

properties and the polyphenols (essential micronutrients) act synergistically

with ascorbic acid (vitamin C), improve resistance to infection. Green tea is

also high in folic acid.”

The article continues:

“Green tea is the cup that cheers,” for aiding digestion, normalizing

thyroid function, protects against leukemia after exposure to radiation…”

The latest research finding suggests that green tea consumption forestalls

development of prostate cancer and inhibits tumor growth.

A 1991 Japan tea symposium hailed “the green” benefits even more.

Scientists have proven that “consumption of the phenols inherent in green

tea will destroy free radicals (those atoms in the body missing an unpaired

electron that cause diseases), making the micronutrients in green tea ideal

antioxidants, meaning the properties in green tea act as a disease preventative.”

(Professor Hasan Mukthar, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland/Ohio) During

a subsequent tea forum in Shizuoka, Japan in 1999, Professor Mukthar concluded

by saying:

“…thus, medical research is confirming the ancient oriental wisdom,

that therapy for many diseases may reside in a teapot.”

A cup of Camellia sinensis, anyone?

Category: Chinese Culture