“Few other cultures are as food-oriented as the Chinese,” said

K.C. Chang, the editor of Food in Chinese Culture.” (New Haven, Yale

University Press, 1977) Why does Chinese food have such universal appeal?

Granted, most of the delectable food served in Chinese restaurants in the

U.S.A. is actually festival food and not representative of the daily Chinese

diet. But what makes Chinese food so tasty? Why has its popularity lasted

so long, and why have the types of food served and their methods of preparation

not changed much for hundreds of years? Quick cooking of seasonal foods

over an intense heat source, flavored and perfectly spiced, makes for tasty,

healthful meals.

A healthy Chinese diet is based on much more than mere nutritional considerations

that are so important to diet-conscious Westerners. Food for the Chinese

is part of their culture, their heritage, closely linked with medicine and

even the arts and politics of the ancients. Legend has it that Lao Tzu once

said, “Governing a great nation is like cooking a small fish, ”

implying that governing a country requires just the right amount of seasonings

and adjustment of preparations for a successful result.

Yi Yin, one of the ancient Chinese scholars who lived during the Shang

Dynasty era, (1500 to 1000 B.C.) was conscious of nutritional values of

foods and had expounded on the theory of relationships between different

food attributes. This renowned scholar noticed a connection between the

five flavors of sweet, sour, bitter, piquant and salty and the nutritional

needs of the five major organ systems, the heart, liver, spleen, lungs and

kidneys. Another source tells us that cooked scallions, (known as green

onions to most of us), fresh ginger root, garlic, dried lily buds and tree

fungus (a mushroom, sometimes sold in the U.S. as “cloud ears”),

consumed in the right amounts and correct proportions, have properties that

ward off certain diseases.

Foods that are said to ward off diseases are also found in the West. Most

American are familiar with the adage, “An apple a day keeps the doctor

away.” Nutritional sleuths have discovered that the pectin in apples

is one of those substances that protect certain body systems. Carrots are

valued for their high vitamin A content. In the Western scientific view,

vitamin A destroys “free radicals” in the body that cause diseases.

Considering the two previous notions, it becomes evident that food has

far more significance than merely keeping the stomach filled. Academicians

from many areas and disciplines consider food in Chinese culture so important

they hold a “Symposium on Chinese Dietary Culture” somewhere in

Asia each year, an event presented by invitation only. The presenters and

their topics vary from year to year, but experts do address such diverse

issues as “Chinese Dietary Culture from a Global Perspective,”

“the Influence of Chinese Culinary Culture on the World,” “Tea-Drinking

Lifestyles among Ming Dynasty Literary Groups,” “ The Originas

of Fermented Food and Drink in the Orient,” “On the Scientific

and Artistic Characteristics of Chinese Dietetics/Culture,” and others.

Looking at these topics demonstrates that these ancient traditions are

still applicable to present-day Chinese food – the growing, distribution

and consumption of foodstuffs in China.

Is the consumption and preparation of certain foodstuffs the same all over

the vast nation of China? The answer is a definite NO! Why? For many reasons!

China and her people have a long history of ethnic diversity. The population

is comprised of varying races and belief systems (many Muslims in the north-east;

some Jewish people; a sprinkling of Christians), all of which had and still

have a strong influence on food preferences. The other contributing factors

relating to China’s culinary differences are equally complex: only

8% of China’s landmass is arable; strong climatic variations from subtropical

to an almost Siberian landscape; huge windstorms in the Mongolian Steppes;

deserts and also a frequent shortage or lack of water for domestic and animal

consumption present a myriad of logistical problems.

One has to only look at a topographical map of China and consider latitudes

and longitudes to become quickly aware of what can be grown where, and how

to accomplish it, more or less successfully. Sixty-three percent of China

today is still rural, in spite of urban headlines that scream of China’s

economic accomplishments. Individually owned farms, heavily taxed and subject

to an arbitrary “fee” system, are tiny – many of them a mere

6 mu (1 mu = 0.165 acres). Farmers, for the most part, grow only enough

to sustain their own families. Such small plots of land make it uneconomical

to raise large livestock. Poultry and an occasional pig are the preferred

food animals. The bulk of China’s wheat crops are grown in the northern

part of the country, and not sufficient at that. China imports immense quantities

of wheat from other nations, mainly from the U.S. and Canada. The south

of the country is “the rice bowl.”

Seafood from the oceans, lakes and river systems contribute important protein

to the diet, but their preparation and those of other foodstuffs vary greatly

according to regional preferences and the seasons of the year. All manner

of living things supply additional protein to the Chinese diet, things from

which most Westerners would recoil (soy bean curd being an exception) –

such as snakes, rats, insects, dogs, cats, civet cats (a species of weasels,

the SARS carriers) and all manner of birds. A Chinese friend told me once

that, “the only things that cannot be flavored are dog’s hearts

and wolf’s lungs.” Would I stick to plain rice and tofu in that

case? Probably, augmented by a few colorful vegetables, laced with some

of those incomparable Chinese spices and classical sauces. One of my favorite

Chinese books, The Cooking of China, by Emily Hahn, time/Life Books, N.Y.

1968, features this quote, “Mounting on high I begin to realize the

smallness of man’s domain; gazing into the distance I begin to know

the vanity of the carnal world. I turn my head and hurry home – back

to the court and market, a single grain of rice falling – into the

great barn.” (Po Chu: I, 772-846 A.D.)

Confucius is supposed to have proclaimed, “A man can never be too

serious about his eating.” Westerners would probably assume this means

“a seriously good meal,” such as perhaps a steak, accompanied

by a baked potato with sour cream, chives, bacon, a tossed salad and a rich

cake desert. That is NOT what Confucius had in mind! Moderation is the key!

Over-consumption of any food, red meat, fats and sugary, highly refined

foods in particular, clog the arteries, which later in life creates all

manner of health problems. It can also lead to obesity. (In ancient times,

sugar was virtually unknown to the people of China. Those who desired sugar

imported it from India. Chinese people sweetened foods with honey). When

I once asked a traditional Chinese medical doctor friend about losing weight

he replied tersely, “No fat, no wheat, no sugar!” I heeded his

advice and within one year had lost 80 lbs. My two years of clinical nutritional

training were not as helpful as this Chinese doctor’s wisdom!

How is one to be serious about food, then, from an age-old Chinese dietary

standpoint? According to ancient tradition, a properly balanced Chinese

meal must have a correctly balanced quantity of both fan (grains and other

starchy foods) and tsai (a combination of vegetable and meat dishes). I

mentioned earlier that Chinese tradition looked upon food not only as something

to fill the stomach, but also as medicine. From where does this theory arise?

Fan and tsai can be classified as belonging to either yin or yang; bodily

functions correspond to those principles, and if the body’s yin and

yang energies are out of balance, problems result, such as illnesses, strange

moods, bad dreams, sweats, and other manner of undesirable physical and

mental disharmonies. Confucius in the Analects, 10:8 also said the following,

“Do not…eat your fill of polished rice, nor finely minced meat;

eat not rice that has gone sour or fish or meat that has spoiled…Do

not eat, except at proper times… never drink wine to the point of becoming

confused… Never consume wine or dried meat brought from a shop.”

Such wisdom in the 6th century B.C!

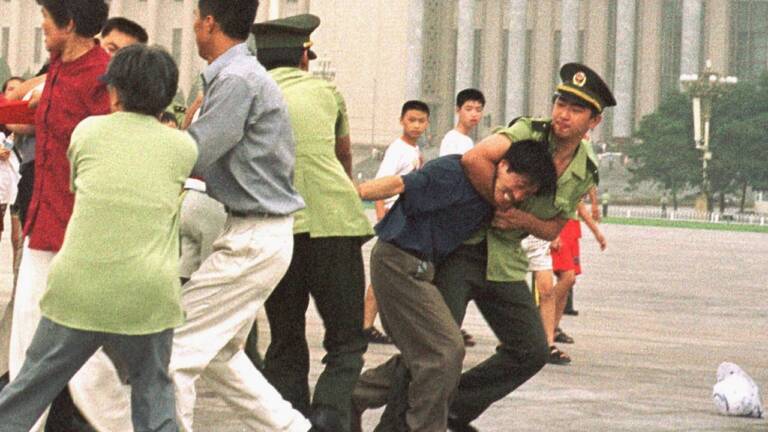

Confucius, that well-beloved sage, pronounced other great ideas such as

this one, “[Good] health is guaranteed if a moral life is led,”

He did not include the effects of karma from previous lives on present health;

the cause-effect relationship between these two may be found in a marvelous

book, Zhuan Falun, by Li Hongzhi. Confucius did say that kindness, justice,

proper behavior, sound judgment and personal integrity, in addition to wholesome

foods, assure health as well. Lao Tzu, on the other hand, proposed that

the concept of The Three Jewels – compassion, humility and moderation –

as well as following natural law, when combined with non-assertive actions

and with simplicity of conduct would lead to balance of the yin (female;

dark) and yang (male; light) and result in a healthful body state.

These historical Chinese “Prescriptions for Living,” relating

to wellness, medicines and dietary practices have been echoed during ancient

Mediterranean and India times as well, although, as one contemporary American

scholar had said, “Only six specific terms are common to all: gender

(male/female); presence or absence of light (light/dark); moisture (dry/wet);

moral value (good/evil); energy (strong/weak) and temperature (hot/cold).”

(Quotes from Grivetti, Louis; “Food History of China,” 2001 lecture;

legrivetti@ucdacis.edu ).

Do these ancient relationships, between our food consumption and how we

live and act, still hold value for us today? Even if the notions of yin

and yang are foreign and meaningless to most contemporary Americans who

are unaware of ancient Oriental cultures and how they relate to the total

person – body, mind and spirit – they deserve consideration. The

2500-year-old Chinese dietary-medical system has been maintained and sustained

for three millennia or longer. Such heritage bears merit. To quote a source

that professor Grivetti, cited in one of his lectures: “Nature has

fours seasons and five elements; climate; the four seasons; and five elements,

wood, water, metal, fire and earth. Always be mindful of weather and the

seasons. To grant a long life, the fours seasons and five elements store

the power of creation within attributes of cold, heat, dryness, moisture

and wind. Man has five viscera – liver, stomach, heart, lungs and kidneys,

in which these five climates are transformed to created joy, anger, sympathy,

grief and fear.” (Nei Ching, 1966, pp 177)

The gremlins that tear at our emotional fabric – the joy, anger, grief,

sympathy and fear- are the very culprits which, for eons, have created havoc

in people’s lives! According to ancient Chinese and Indian/Mediterranean

culture, dietary practices influence our whole life systems. What we eat,

how we eat it and how much of what we eat all have a bearing on our health

and how we think and act. Each one of us has an incredible, awesome, Spirit-given

power to make choices and act on the decisions we make. How we think and

act will determine how we die and whereto we journey after we are gone.

Let’s make it a great journey.

Category: Insights