The Hong Kong Government should rethink proposed harsh new security

laws.

As the Union Jack was lowered for the last time in Hong Kong, the

British

governor, Chris Patten, declared: “Now Hong Kong people are to run Hong

Kong. That is the promise. And that is the unshakeable destiny.” Beijing

was

never going to let that happen fully on the issues that mattered –

security,

sovereignty and political freedom. In his speech on that wet night six

years

ago, then Chinese president Jiang Zemin spoke of the colony’s “return to

the

motherland” while making soothing noises about China’s commitment to the

principle of “one country, two systems”.

Hong Kong has since taken a battering on several fronts. It was hit hard

by

the Asian economic crisis that set in within weeks of the handover.

Rising

unemployment, business collapses, a decline in tourism and, most

recently,

the SARS epidemic have added to its woes. On top of this, Hong Kong’s

administration has moved to introduce anti-subversion laws that could be

used to stifle criticism of both the local and mainland rulers.

The anti-subversion laws, grouped under what is known as Article 23,

would

form part of Hong Kong’s Basic Law, the “mini-constitution” that governs

the

territory under the “one country, two systems” regime.

The law is currently before a local legislature stacked with

pro-Government

and pro-Beijing members. Article 23 covers such activities as treason,

subversion and secession, sedition, theft of state secrets and

prohibitions

on organisations with foreign links from conducting political activities

in

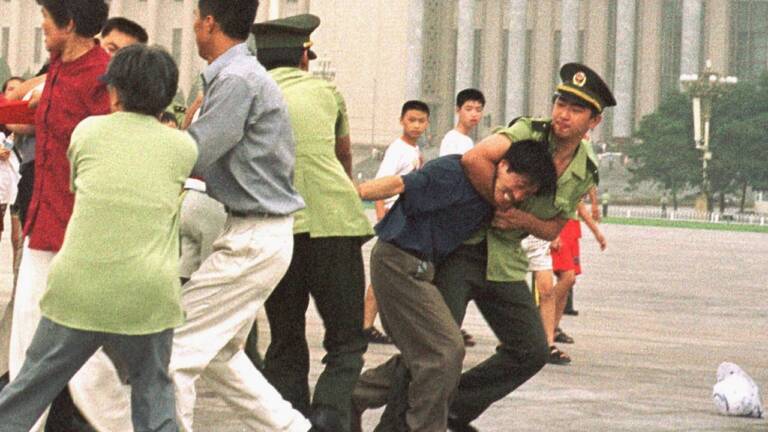

Hong Kong. Critically, it would mean that organisations banned in

mainland

China could not operate lawfully in Hong Kong. This would include groups

such as Falun Gong and could potentially be extended to include

churches,

human rights groups, trade unions and even opposition political parties.

Opponents say there is a direct threat to political, religious and media

freedoms.

The Hong Kong Government contends that Britain, Canada and the United

States

already have legislation similar to Article 23. But it fails to point

out

that these countries also function under a rule of law not apparent in

China, where what constitutes a state secret, for example, is a rubbery

concept.

The US, Britain and the European Union have all criticised the proposed

law.

The Hong Kong Government has also been taken aback by the level of

public

opposition. On Tuesday up to 500,000 black-clad citizens – from a

population

of just 6.8 million – peacefully took to the streets in the largest

protest

in China since the 1989 pro-democracy demonstrations.

The catalyst for the protest was Article 23, but demonstrators also

vented

frustrations over the administration’s handling of the economy and the

SARS

crisis. Hong Kong’s Government should rethink its anti-subversion laws,

but,

under pressure from its mainland puppeteers, probably will not.

http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2003/07/02/1056825454606.html

Posting date: 3/July/2003

Original article date: 3/July/2003

Category: Media Report