As SARS rages in China, some cadres

are more intent on saving face than saving lives. TIME investigates a cover-up

that may have killed

BY Hannah Beech/ Shanghai

Photo taken in Shanghai on April 16. AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko. Because of the government’s deliberate cover-ups, more and more Chinese people’s health is in jeopardy without being aware of it. |

This is the hospital ward China’s Ministry

of Health doesn’t want you to see. There are more than 100 Severe Acute

Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) patients crammed into tiny rooms in the infectious

diseases section of Beijing’s You’an Hospital. “Every single one

of us in this building is a SARS patient,” says a nurse surnamed Zhang who

worked at the People’s Liberation Army Hospital (P.L.A.) No. 301 until

11 days ago, when she was diagnosed with the disease and admitted here.

“There are at least 100 SARS patients here, if not several hundred. The

conditions here are really bad. We’re not allowed out of this room.

We piss in this room, crap in this room and eat in the room. As far as I

know, at least half of the patients here are doctors and nurses from other

hospitals.” As a Time reporter continued through the ward, another nurse

who wouldn’t give her name stopped him and explained, “Look, I’m

not pushing you away. I do this for your own good. It’s too dangerous

here. It’s really a terrible disease, even we who work here don’t

know when we’ll get it. No place is safe in this hospital. All of these

wards are full of SARS patients, there are over 100 at least. Don’t

believe the government–they never tell you the truth. They say it’s

a deadly disease with 4% mortality? Are you kidding me? The death rate is

at least 25%. In this hospital alone, there are over 10 patients dead already.”

According to the Chinese government, most of

these patients–and perhaps hundreds or even thousands of others across

the nation–simply do not exist. Before the reporter is hustled out of You’an’s

teeming isolation ward, nurse Zhang warns, “Never believe what the Health

Ministry tells you.”

China, flush from having won the right to host

both the Beijing 2008 Olympics and the 2010 Shanghai World Expo, may be

presenting a rosy, reformist face to the rest of the world. But the country’s

handling of the deadly SARS epidemic, which is believed to have originated

in the southern province of Guangdong last November, shows that behind closed

doors Beijing can be as inscrutable and secretive as ever. Numerous reports

from local doctors over the past week suggest that the nation’s health-care

system remains hostage to a government that values power and public order

before human lives. “You foreigners value each person’s life more than

we do because you have fewer people in your countries,” says a Shanghai-based

respiratory specialist, who sits on an advisory committee dealing with epidemic

diseases. “Our primary concern is social stability, and if a few people’s

deaths are kept secret, it’s worth it to keep things stable.”

The question is: Just how many deaths can be

kept secret before the health epidemic itself becomes a threat to social

stability? For decades, China’s Ministry of Health has deliberately

kept killer outbreaks hidden, hoping that deadly diseases will burn out

on their own without interference, or scrutiny, from the international medical

community. After all, China is a big country, it says, and it’s natural

for a case or two of plague or rabies to pop up; why worry the populace

unnecessarily? But Beijing’s emergency plan may be backfiring with

SARS, which has burst out of the mainland’s national boundaries to

kill 116 people and infect 2,890 worldwide as of last weekend. Yet even

as the deadly pneumonia proliferates around the world–Africa is the latest

continent afflicted with the bug–China continues to massively underreport

its own SARS epidemic. In the metropolises of Beijing and Shanghai, local

doctors and nurses whisper of hundreds of cases piling up in epidemic wards.

And citizens who have put faith in China’s health-care system for decades

are beginning to wonder whether their long-held trust has been dangerously

abused.

A boy in Beijing covers his eyes with respirator. |

Even as late as last Saturday, China’s health

authorities continued to stick to an accounting of 60 SARS deaths and 1,300

cases–even though China’s Premier Wen Jiabao visited You’an Hospital,

where medical staff say the full caseload there has not been incorporated

into the figures. In an effort to ease an increasingly worried populace,

Beijing’s recently appointed Mayor Meng Xuenong claimed last Thursday

that Chinese health officials have “full control over atypical pneumonia.”

Meanwhile, medical authorities maintained that most SARS cases in China

outside of Guangdong were “imported,” proving that cities such as Beijing

and Shanghai were not themselves breeding grounds for the disease.

But even as the government continued its policy

of denial, a number of whistle-blowers began contesting Beijing’s numbers.

On Tuesday a retired military hospital surgeon alleged that in one Beijing

hospital there were more than 60 SARS patients and seven deaths from the

disease. A local cadre from Shenzhen told Time that during an internal meeting

last week, a city health official spoke of at least six deaths there so

far while still publicly denying any cases. And in Shanghai, local doctors

spoke of 14 cases at one hospital, while Dr. Li Aiwu of the Shanghai Pulmonary

Hospital confirmed that seven foreigners were being treated for the disease–contradicting

the city’s previous claim that no foreigners were suspected of having

SARS. “I guess that means I don’t exist,” jokes a middle-age Englishman

who has been confined to its 14th-floor isolation ward for a week.

The Manchester native connects with the outside

world by cell phone. “The care here is good, but I must admit I’m feeling

a little cut off from the real world.”

China’s continued obfuscation contributed

to the U.S.’s issuing a travel advisory warning against nonessential

trips to China. At about the same time, Malaysia barred all tourists from

mainland China and Hong Kong. In Hong Kong, the government reacted to the

continued increase in local SARS cases and criticism it had been slow in

dealing with the disease by finally ordering household contacts of confirmed

patients to stay in home quarantine. Travelers wishing to fly from Hong

Kong’s Chek Lap Kok airport would also have their temperature taken

before they were allowed to board their flights. In the mainland, luxury-hotel

occupancy in Shanghai has slipped from the usual overbooked 120% this time

of year to 30%. High-level trips by former U.S. President George Bush, Singaporean

Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong and a World Economic Forum event have been

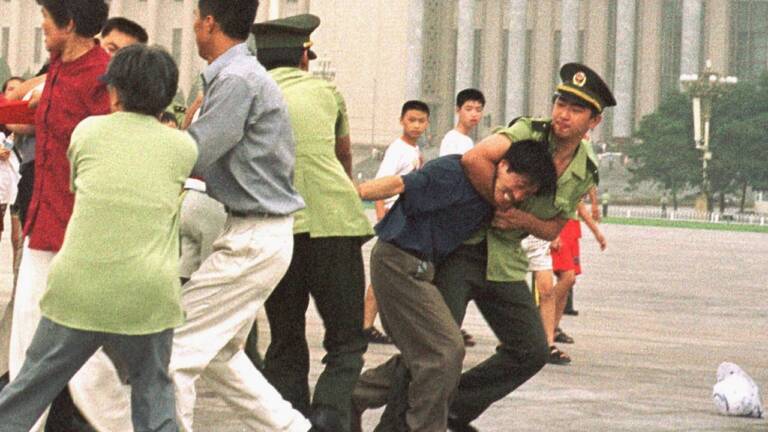

postponed or canceled. “The drop-off in visitors is worse than in 1989,”

grumbles a Shanghai foreign-affairs official, referring to the foreign exodus

after the Tiananmen crackdown.

In a country where mass revolts have regularly

paralyzed empires and regimes, the Communist Party is apprehensive about

panicking the people. And now that China’s booming economy is more

dependent than ever on foreign investment–54% of Shanghai’s industrial

output, for instance, derives from foreign-owned or partially foreign-owned

companies–the Party is doubly concerned about maintaining the appearance

of stability. “Look at what happened in Hong Kong, where everybody’s

scared and wearing a mask,” explains a senior aide to Shanghai’s vice

mayor, blaming the foreign media for stirring up jitters about the killer

virus. “We don’t want everyone to get panicked like that for no reason

and destroy our economy.” Furthermore, with the major May 1 holiday week

rapidly approaching, local tourism officials are worried that the SARS scare

will deter Chinese from traveling and spending their yuan.

China has a long history of not facing up to

its medical problems. Prior to SARS, the country had been notoriously unwilling

to publicly admit to its burgeoning AIDS epidemic. When news trickled out

three years ago of tens of thousands of farmers in central China infected

by HIV after selling blood to traffickers using tainted equipment, the government

delayed more than a year before conceding the truth. Even then, Beijing

insisted the virus contaminated only one tiny village in Henan province.

Finally, in 2002, the Chinese leadership revised its HIV estimate from 30,000

cases to 1 million–in a single day. Similar night-and-fog tactics kept

quiet an outbreak of food poisoning in the northeastern province of Liaoning

last month, when three schoolchildren died and 3,000 were sickened after

drinking tainted soy milk. Even with hundreds of students flocking to hospitals,

local authorities denied for weeks that there was anything amiss.

Most doctors are too frightened of losing their

jobs to tell the truth about such cover-ups. A doctor who told a TIME reporter

that there were dozens of SARS cases being isolated in a tuberculosis ward

at Beijing’s No. 309 People’s Liberation Army Hospital backed

out of continuing the discussion, saying, “I’m embarrassed that I can’t

talk to you. I had really wanted to, but I’m young and I can’t

afford to lose my job.” But other brave souls are finding the courage to

speak out. Last week, in a case first reported by Time, retired military

surgeon Jiang Yanyong alleged that at the same hospital there were 60 SARS

cases and seven deaths, and that at the P.L.A.’s No. 301 Hospital (where

nurse Zhang works) at least 10 doctors and nurses had contracted the disease

from their patients. Jiang, who initially submitted his statement to the

state TV channel CCTV 4 but received no response, says he was spurred to

report more accurate numbers because he was so dismayed that the Ministry

of Health reported only 12 cases and three deaths in the capital in early

April. According to Jiang, another military hospital, No. 302, admitted

two SARS patients first diagnosed at No. 301 in early March just as Beijing

was convening the politically sensitive National People’s Congress.

It was only after both patients had died, says Jiang, that health authorities

called a meeting, but instead of instructing doctors on how to contain the

disease through public-education campaigns, Jiang says medical officials

told physicians they were “forbidden to publicize” the SARS deaths “in order

to ensure stability.”

Doctors in Shanghai have faced similar political

interference. Early last week, physicians at a hospital in the city’s

Huangpu district were called in by their superior to discuss a new policy

initiative straight from the municipal health bureau. For the past couple

of months, doctors had been clandestinely searching the Internet for information

about SARS, and they hoped for solid information from their director. Instead,

he told them not to wear masks in the hospital, save in isolation wards

and a few select diagnostic rooms. The gathered physicians were confused.

One top administrator meekly said, “I thought wearing masks was supposed

to stop SARS from spreading to medical staff.” Their superior responded

curtly, “Wearing a mask will scare the patients. We do not want panic, especially

since SARS has already been controlled.”

Local health authorities can get away with such

reckless policies because there’s little oversight from above. Health

Minister Zhang Wenkang actually ranks lower in the government hierarchy

than the Communist Party secretaries of Shanghai and Guangdong. That gives

the regional Party bosses far more power than the Health Minister to dictate

even medical policies in their fiefdoms. Furthermore, each city’s center

for disease control (CDC), which is responsible for updating China’s

SARS caseload, reports first to the local Party boss, then to the Ministry

of Health. The head of each city’s local health bureau is appointed

by local Party cadres, not by the Ministry of Health. That structure means

local health workers have little incentive to reveal the true magnitude

of the crisis.

Even doctors on the front lines have been left

in the dark, sometimes to their detriment. At Beijing’s You’an

Hospital, for instance, nurse Zhang estimates that about half of those in

the isolation ward are medical staff from other area hospitals. To complicate

matters further, the only people who are officially allowed to diagnose

SARS in China are CDC researchers, not the physicians who are treating the

patients. “I had a patient whose symptoms clearly seemed to be those of

a SARS-positive patient,” says a doctor who consults at a hospital in a

leafy district of Shanghai. “But after I contacted the CDC, the patient

was suddenly transferred without my knowledge and I never found out whether

he had the disease or not.” The physician presumes the patient did indeed

have SARS; otherwise, why would he have been transferred so mysteriously?

“We doctors are all left with a lot of questions,” he says. “I think it’s

shameful to not let us know what’s going on.” That information blackout

has resulted in unnecessary deaths as local doctors have resorted to trial-and-error

treatments rather than using therapies that have proved relatively effective

in other hospitals. Physicians in some Guangdong hospitals, for example,

were told by Beijing to treat SARS patients for mycoplasma pneumonia and

chlamydia pneumonia, which are bacterial infections, even though they had

already found that a combination of antiviral medications and steroids showed

better results.

Part of the confusion might be springing from

China’s accounting methods. Current diagnostic tests for SARS are unreliable

at best, and doctors worldwide have had to diagnose primarily by evaluating

symptoms and proximity to other SARS patients. But with places like Beijing

refusing to acknowledge true numbers of infected patients, it becomes difficult

to prove that a person has been near a SARS patient, because those victims

aren’t supposed to exist in the first place. That, plus a more stringent

set of requirements applied before confirming a case as SARS means that

many patients who would be diagnosed as having the virus elsewhere in the

world are only considered “suspected” cases in China. The English patient

at the Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital, for instance, has been quarantined for

a week, yet the physicians there have told him there’s no way they

can tell whether he has SARS. “I’ve heard that in other countries they’re

able to diagnose within a few days,” he says, between dry coughs. “Why can’t

they diagnose our cases? It’s very strange.” (The Englishman’s

doctor says he is treating the man’s case as SARS, although the CDC

has yet to confirm the case as such.)

Last Thursday it seemed the Ministry of Health

couldn’t even agree on its own SARS count. At a press briefing in Beijing,

Qi Xiaoqiu, director of the Ministry of Health’s Disease Control Department,

said China’s official SARS statistics include “confirmed and suspected

cases.” Just minutes later Vice Minister of Health Ma Xiaowei told reporters

that the numbers he had stated referred only to confirmed cases. Either

way, experts agree that the ministry’s reckoning still seems far too

low. Mainland doctors fret that with continuing ignorance about the disease,

the virus could spread even farther. Misinformation abounds: a Shenzhen-based

health official named Zhang Shunxiang warned last week that people shouldn’t

wear masks because they impede proper breathing and contribute to public

panic–contrary to advice given almost everywhere else in the world. State-run

newspapers in the mainland suggested that a protein-rich potion containing

cicada shells and silkworms could be a SARS panacea. Even more worrisome

is the possibility that the disease is making its way into China’s

estimated 100 million-strong migrant worker community, which has little

access to health care. Already, doctors suspect that the first case of SARS

in Beijing was a migrant who worked in Guangdong. If the virus is indeed

infecting members of China’s vast floating population, experts fear

it could spread quickly into the country’s undeveloped interior. With

much of China still in the dark about the killer bug, the worst may be yet

to come.

—-With reporting by Bu Hua/Shanghai and Huang

Yong

http://www.time.com/time/asia/magazine/article/0,13673,501030421-443226-1,00.html

Posting date: 19/Apr/2003

Original article date: 18/Apr/2003

Category: Media Reports