CHINA’S COMMUNIST leadership has spent the past few days bombarding the

country’s long-suffering population, and anyone in the outside world who

will listen, with skull-numbing speeches about the supposed

philosophical

breakthrough of President Jiang Zemin. In fact his “Three Represents”

policy

is bold, but not particularly philosophical or hard to explain: It

pragmatically proposes that the Communist Party preserve its

dictatorship by

co-opting the business elite that increasingly drives the country’s

economy.

Party leaders have been duly unveiling concessions to their new

clientele at

the party congress, promising to allow entrepreneurs more access to

capital

and better terms for competing with state-owned industry. Otherwise the

congress has been striking mainly for the absence of meaningful

political

debate and the secrecy shrouding any real decision-making.

Though Mr.

Jiang

and other senior leaders are expected to step down from their party

positions tomorrow and be replaced by a new generation of leaders, there

has

been no discussion, during the many hours of televised proceedings, of

the

change or how it was decided.

Some see the leadership transition from Mr. Jiang to successor Hu Jintao

as

a modest step forward, because it is the first in Communist Chinese rule

not

precipitated by a leader’s death or accompanied by violent upheaval. Mr.

Jiang is credited with having established a powerful consensus during

his 13

years in office behind policies of rapid economic modernization, the

embrace

of global capitalism and the maintaining of stable relations with the

United

States. Little is known about Mr. Hu and the other new leaders, but they

are

widely expected to continue this course. Yet Mr. Jiang, who will retain

considerable influence through allies he has installed in the party

Politburo, has also frozen what had been a slow crawl toward greater

democracy by the Chinese leadership before 1989. His alternative is the

cozy

alliance between bureaucratic and economic elites, shielded by an

authoritarian umbrella, that for decades has served such regimes as

Malaysia

and Singapore — not to mention Taiwan before its recent

democratization.

So far this seems to be working reasonably well: Chinese growth remains

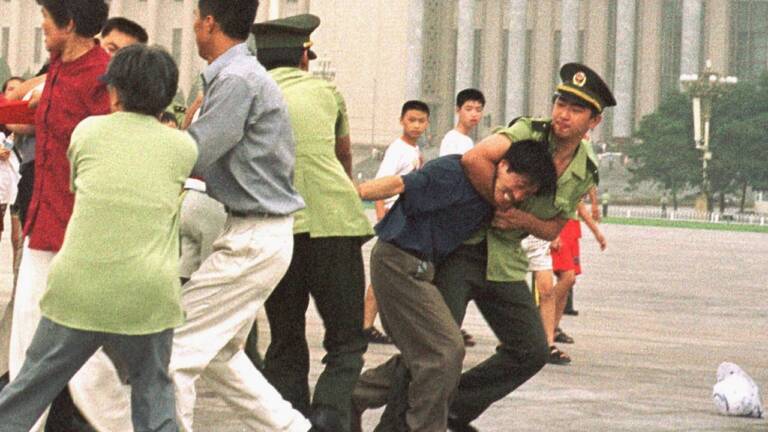

high, foreign investment is pouring in, and dissident movements such as

the

Falun Gong religious order have been crushed with relative ease. Yet the

leadership still feels insecure enough to round up dissidents of all

kinds

and ship them out of Beijing before staging its congress. Signs of

potentially serious economic problems lie just below the surface:

Without a

working rule of law, corruption threatens to become overwhelming. So do

the

bad loans by the state-run banking industry, which could bring on a

financial crash if growth should falter. These threats could be greatly

reduced if Mr. Hu were to pursue even modest political liberalization,

such

as greater press freedom, the expansion of multi-candidate elections

from

villages to larger jurisdictions, and tolerance for independent civil

and

religious movements. Such reforms seem to be regarded as too risky by

most

Chinese leaders; yet history — including that of Taiwan — suggests

that

Mr. Jiang’s authoritarian strategy is even less likely to succeed.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A51765-2002Nov13.html

Posting date: 15/Nov/2002

Original article date: 14/Nov/2002

Category: Media Reports & Forum