GEOFFREY YORK from Beijing – The Globe and Mail

Jiang Zemin has never been famous for his modesty. But in his farewell

speech to his party comrades last Friday, when he reviewed his 13 years

at

the helm of China’s ruling Communist Party, his rhetoric was

particularly

florid.

He boasted of leading a “magnificent upsurge” in China’s modernization,

with

a “historic leap” for its people and “tremendous achievements” in rising

wealth and national strength. He bragged that China had nearly tripled

its

GDP during his 13 years in power. He proclaimed that he had written “a

glorious page in the annals of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese

nation.”

Mr. Jiang, the 76-year-old Chinese President and Communist boss, would

prefer to measure his legacy in terms of economic growth and global

prestige

— areas where China has clearly made great gains during his rule. But

a

harsher view of his legacy can be drawn from the latest data on labour

protests, social inequality and unemployment.

Labour disputes have increased by 30 per cent in the past five years.

Discontent over corruption and inequality is growing, with surveys

estimating that 36 million people are “extremely dissatisfied” with

their

life. About 50 million workers have lost their jobs at state-owned

enterprises and municipal work units since 1995. The gap between rich

and

poor is widening. The ranks of the poorest of the poor, with less than

$40

(Canadian) in monthly income, have swollen by at least 10 million since

1996, even as the richest class of people gets richer.

The strange reality of the Jiang epoch is that both of these trends —

the

successes and the dark side, the booming economy and the rising

inequality,

the victories on the world stage and the mounting layoffs at home — are

equally accurate measures of his legacy. They are the yin and yang of

modern

China, the contradictory elements that seem locked inextricably together

as

China races toward an uncertain future.

The era of Jiang Zemin formally ends this Friday, when he retires as

General-Secretary of the Communist Party, the most powerful post in

China,

although he remains President until next March and will continue to

exercise

influence in the party backrooms for years to come.

With his square-rimmed glasses, his nerdy image, his legendary vanity

and

his fondness for crooning Love Me Tender to world leaders during dinners

at

global summits, Mr. Jiang has perhaps never been taken seriously enough.

In

the early years of his rule, most pundits believed he was too weak to

last

more than two or three years, at most.

But instead he became a battle-hardened survivor of China’s backroom

power

struggles. Plucked from obscurity to head the Communist Party in June,

1989,

after his predecessors were judged too soft, he was a former

Soviet-trained

engineer and car-factory manager who had risen to become the Shanghai

party

boss. He consolidated power in the early 1990s as his mentor, Deng

Xiaoping,

slowly succumbed to illness and old age.

After four decades of rule by autocratic strongmen, Mr. Jiang introduced

a

new form of collective leadership. He was not a visionary like Deng or

Mao.

He was a consensus-builder who exercised power by cultivating allies and

manoeuvring shrewdly in the party’s top ranks. His heir apparent,

Vice-President Hu Jintao, has also ascended by avoiding controversy,

forging

alliances, and remaining bland and cautious in his public statements.

After consolidating power, however, Mr. Jiang often behaved like an old

Chinese emperor. He turned apoplectic at the sight of protesters in

Switzerland, berating his hosts and cutting short a ceremony. On

billboards

and posters, he portrayed himself as the equal to Mao and Deng. With his

much-publicized love of poetry and outdoor swimming, he deliberately

sought

to evoke parallels to Mao, who had the same hobbies.

He was the first Communist leader who grew up after the Long March

generation, and the first who lacked any military experience. He was not

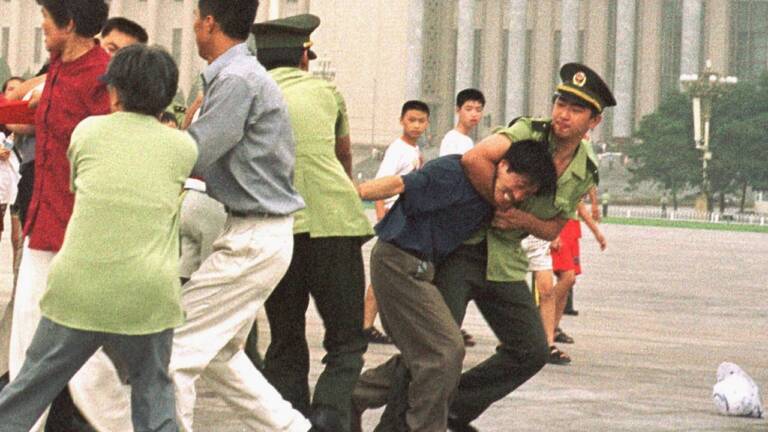

involved in planning the military operation that crushed the Tiananmen

Square protests in 1989. Yet his repression of his enemies was as

relentless

as any of his predecessors, with the possible exception that he

preferred to

jail or exile his opponents rather than shoot them dead. He has arrested

Tibetan separatists and dissidents, crushed new political parties, and

tried

to destroy the Falun Gong religious sect that had challenged his

authority.

While he still recites the slogans of socialism, Mr. Jiang has preferred

to

exploit the much more potent forces of nationalism and patriotism. To

further safeguard his power, he has diligently cultivated the top

officers

of the People’s Liberation Army, giving them higher wages, a bigger

military

budget, and lucrative promotions for his loyalists.

He does deserve credit for keeping China solidly on the path of economic

reform. He has liberated the private sector and helped achieve an

average

9.3-per-cent annual growth rate.

His other triumphs were impressive: getting China into the World Trade

Organization, helping Beijing win the 2008 Olympics, restoring relations

with the West after the post-Tiananmen diplomatic freeze, holding

successful

summits with American and European leaders, supervising Hong Kong’s

return

to Chinese control in 1997, and boosting foreign investment and trade.

But his rule has been tainted by the mounting levels of inequality and

corruption. Despite frequent anticorruption campaigns, he has shown no

ability to solve the problem. His legacy also includes a potential

disaster

in the Chinese banking sector, where corruption and bad loans have

threatened to trigger a collapse, and a growing crisis in the rural

regions,

where millions of peasants are suffering from falling incomes and heavy

taxation.

Over the next few years, Mr. Jiang will retain influence as the chief

arbiter of his clumsily named “Three Represents” theory, which is

expected

to be written into the Communist Party’s constitution at the congress

this

week.

Under this theory, the party should expand its membership to represent

three

major groups: capitalist entrepreneurs, cultural and academic elites,

and

ordinary people who don’t belong to the party’s traditional base of

peasants

and workers. The doctrine is aimed at helping the party to escape

irrelevance by co-opting the growing numbers of rich and middle-class

Chinese.

Mr. Jiang’s Three Represents theory is tirelessly promoted in the

Chinese

media, yet many observers have mocked and ridiculed it, laughing loudly

at a

state television channel that solemnly reported that a village’s

soft-shell

turtles had grown bigger after the villagers had gathered to discuss the

theory.

Even if he lacks a convincing vision, optimists argue that Mr. Jiang has

taken China in the direction of Singapore and Malaysia, where political

authoritarianism is combined with a growing level of social and economic

freedom.

Pessimists have a different analogy. They point to Indonesia, where the

economy grew rapidly for 30 years under the Suharto dictatorship but

weakened when the regime was unable to cope with street protests and

discontent in an era of rising expectations and mounting inequality. The

Suharto regime eventually collapsed — a fate that could someday befall

the

Chinese Communist Party if it ignores the dark side of Jiang Zemin’s

legacy.

Geoffrey York is The Globe’s Beijing bureau chief.

Posting date: 14/Nov/2002

Original article date: 13/Nov/2002

Category: Media Reports & Forum